Using empty shells to study a population of Pacific razor clams in Clam Beach, Humboldt County, California

RESEARCH NOTE

Gabriel Irribarren and Jose Marin Jarrin*

California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, Department of Fisheries Biology, 1 Harpst Street, Arcata, CA 95521, USA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4474-8323 (JMJ)

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4474-8323 (JMJ)

* Corresponding Author: jose.marinjarrin@humboldt.edu

Published 4 Nov 2024 • doi.org/10.51492/110.15

Key words: Pacific Ocean, data-poor fisheries species, Humboldt County, monitoring, Pacific razor clam, Siliqua patula

| Citation: Irribarren, G., and J. Marin Jarrin. 2024. Using empty shells to study a population of Pacific razor clams in Clam Beach, Humboldt County, California. California Fish and Wildlife Journal 110:e15. |

| Editor: Kim Walker, Marine Region |

| Submitted: 25 March 2024; Accepted: 2 July 2024 |

| Copyright: ©2024, Irribarren and Marin Jarrin. This is an open access article and is considered public domain. Users have the right to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles in this journal, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, provided the authors and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife are acknowledged. |

| Funding: This project was funded with a CSU Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology (COAST) Undergraduate Student Research Support Program and Cal Poly Humboldt Marine & Coastal Science Institute Undergraduate Student Research Award to Gabriel Irribarren. |

| Competing Interests: The authors have not declared any competing interests. |

The Pacific razor clam (Siliqua patula) is a sought-after clam for consumption by recreational and commercial fishers (Sims 1960; Hiebert 2015). It is found on North America’s west coast, ranging from Pismo Beach in California to the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. Pacific razor clams typically inhabit low intertidal to subtidal zones on flat sandy beaches with strong surf. They begin reproducing during their second year of life and have been found to live up to 15 years in Alaska. Within the clam’s southern range, their lengths span from 8 to 15 cm, while reaching up to 28 cm in Alaska (CDFW 2020).

These clams have been and still are a significant food resource for some western Native American tribes (Berger 2017). As European settlers reached Humboldt in 1806, they were greeted with a feast of clams (Wiyot Tribe n.d.). Over the next few centuries as more people emigrated from the East, they adopted the practice of fishing for multiple species of clams, including razor clams, which are still harvested to this day. As the popularity of fishing/harvesting for Pacific razor clams has grown, recreational fishers have seen their populations dwindle. State and province managers throughout its distribution have developed regulations surrounding the harvesting of Pacific razor clams to reduce the risk of overfishing. In California, there are no commercial fisheries allowed for razor clams; however, recreational fishers are limited to 20 clams per day and closures of beaches or parts of beaches depending on location (CDFW 2023). Besides being prey for Dungeness crabs and other benthic and demersal foragers, they are ecologically important as filter feeders on phytoplankton, connecting the pelagic and benthic components of the water column by excreting onto the sediment. Pacific razor clams are also known as indicator species of ecosystem health due to their relatively sedentary lifestyle, allowing them to bioaccumulate contaminants and pathogens (Bowen et al. 2020).

Clam Beach in Humboldt County, California, contains one of the southernmost populations of Pacific razor clams, and the largest in the state of California, which is important for recreational fishing/harvesting and cultural practices. Fishers in California are required to possess a fishing license and follow general clam regulations (Cal. Code Regs, § 29.20) to fish them, but the fishing efforts, abundance and general biological parameters of Pacific razor clams are not currently being monitored (CDFW 2023). Due to high levels of domoic acid, beaches in Humboldt County were closed to the fishery from 2016 to 2021, which protected the populations from fishing pressure. However, California sandy beaches are being impacted by increasing sea-surface temperatures, sea-level rise, larger waves, and, in general, changes to coastal oceanography produced by Global Climate Change (Bowen et al. 2020). Therefore, regular monitoring of this population is necessary, which can be cost prohibitive.

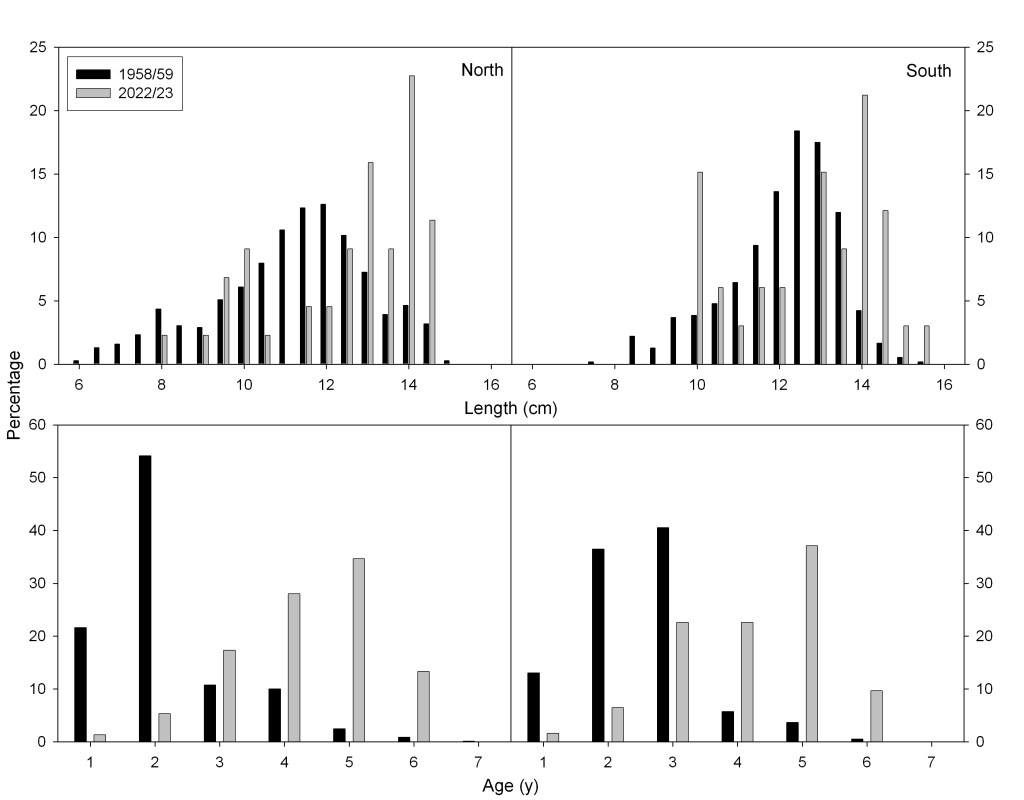

The last thorough study of the Clam Beach population was in 1958 and 1959 (January through August) where the objective was to understand growth characteristics and life history in terms of spawning, time of maturity, and mortality while also evaluating the “annual ring” aging method and determining the number of diggers utilizing the fishery at Clam Beach (Sims 1960). To carry out this objective, among other parameters, the abundance, length, and age were estimated on the north and south sides of the beach by digging up individuals and interviewing clammers (Sims 1960). For management purposes, the beach is divided into the northern (~3.70 km long) and southern sections (~1.66 km long), with the southern parking area of the Clam Beach County Park as the geographical boundary (40.9945, –124.1143; Fig. 1). The northern section is open to digging on even-numbered years, and the southern side on odd-numbered years. To estimate the age of the clams, Sims (1960) counted the number of growth rings under the periostracum (skin), a method that has been found to be effective for aging clams and is known as the “annual ring” method (Weymouth 1923). This is a method based on other aging/growth patterns seen in nature such as otoliths and scales in fish, and annual rings in trees (Weymouth 1923). Sims (1960) monitored 26 “clam-tides” (tide of 0.0 m or less during daylight hours) in 1958 and 27 “clam-tides” in 1959 where he observed a significantly higher average catch-per-unit-effort in the north than in the south side (15.8 vs. 7.4 clams per digger per low tide). The range of the length of the clams was 5.7–15.1 cm (median = 11.2 cm), and 7.2–15.0 cm (12.2 cm) on the north and south side, respectively (Fig. 2). As for the age range, the clams were from 1 to 7 years (median = 2 years), and 1 to 6 years (3 years) on the north and south side, respectively (Fig. 2). During these years, water temperature averaged 11.8 ± 1.5 °C in 1958 (9.9 to 11.8 °C) and 10.7 ± 1.1°C (±SD) in 1959 (8.6 to 15 °C).

To monitor the Clam Beach population, we collected empty shells to estimate the abundance, length, age, and growth rate of razor clams (Szarzi 1991). This is in comparison to catching live clams, which would be more invasive and cost prohibitive way due to removal of clams (most do not survive being dug up), cost of gear, and staff salary. We also used these data to compare the individuals on the north vs. south sides of this beach during 2022–2023. Finally, we compared our data to Sims’ (1960) to explore how the population has changed over time. However, because we used empty shells and could not pinpoint where the clams lived and we assumed that smaller shells would be broken more easily than larger shells, we only compared our maximum length and age data with Sims’ (1960). Besides collecting empty shells, we also measured water temperature (°C) and counted the number of clam diggers.

We collected data at Clam Beach, in Humboldt County, California from October 2022 to March 2023. To count and collect shells, one person walked parallel to the shoreline during the lowest tide of the day at the high tide line, and observed 2 m on either side of an imaginary transect line for one hour (2.4–5.6 km), tracking the distance walked in meters with the Strava cell phone app. These transects were carried out on six different days, three times towards the north and three towards the south for a total of six transects. The starting place of the transects was always the southern parking area/entrance of Clam Beach, which divides the beach into the north and south sides used for razor clam fishing regulations (40.9945, –124.1143; Fig. 1; CDFW 2023). Prior to carrying out the transect, we measured water temperature (°C) at shin-high depth using a handheld Eco Sense EC 30 A. Only shells with both halves and with at least one half that included the umbo and edge (broken or unbroken) were considered to reduce the possibility of counting the same individual (empty shell) more than once. Due to time constraints, we only collected empty shells and brought them back to the lab during the first four transects for length measurements and aging. In addition to counting and collecting shells, clam diggers fishing/harvesting razor clams were counted during the transects.

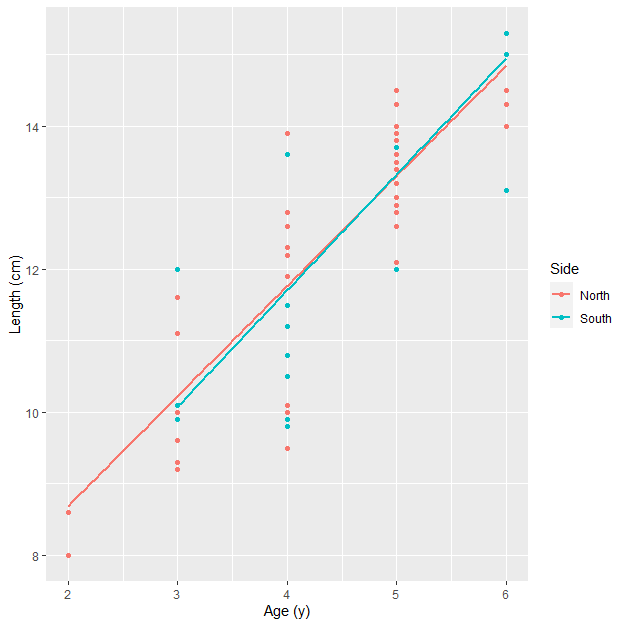

In the lab, we cleaned all shells and sorted by whether they could be measured and aged (unbroken shells) or just aged (broken shells with umbo and edge). The total length (maximum length from one edge to the other) of all unbroken shells was measured in centimeters using a standard ruler. We estimated the age of the clams by counting the brown and black bands formed by fast and slow growth periods, respectively (Sims 1960). The combination of both bands was counted as one year. To confirm the age, we removed the periostracum (skin) to uncover thicker dark bands and thin white lines formed annually. The thin white lines are usually found under the black bands. To test the accuracy of our age estimates, one person read all the shells two times (at least 15 days apart), without looking at the previous readings, and calculated the coefficient of variance between the two readings (CV = 7.72%, SD = 10.33). For shells where the two readings did not match, that same person carried out a third reading, to determine which of the first two readings was correct. To test the precision, the ages were correlated to the length as older clams should also be longer (Fig, 3). However, this assumption can be unmet if some clams experience very low growth rates.

We calculated growth rates (cm per year) as the slope of regressions between empty shell length and age (Fig. 3). We compared the abundance of empty shells (number of shells per 1 km2), shell length, and age of clams between the south and north sides of the beach during 2022–2023 using two-sample t-tests assuming unequal variances. Growth rates between the two sides of the beach were calculated and compared with an Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA), with shell length as the independent, age as the dependent variable and the side of the beach as the covariate. ANCOVA assumptions were met and tested using Bartlett tests and QQ plots. Finally, to explore how the population has changed over the last 60 years, we compared the absolute values of maximum length and age of our data vs. Sims’ (1960) without the use of statistics, because they were only one data point each.

We counted a total of 615 shells, 370 on the northern side and 245 on the southern region of the beach with a median abundance of 66 shells/km2 in the north and 62 shells/km2 in the south (Fig. 4). Water temperature averaged 13.2 ± 1.2 °C (11.5–14.6 °C) and no clammers were observed during any of the six transects completed. From the first four transects, we were able to measure the total length of 77 unbroken shells (44 north and 33 south) and estimate the age of 137 unbroken and broken shells (75 north and 62 south) (Fig. 2). The length and ages of shells collected on the northern end were between 8 and 14.5 cm (median = 12.8 cm) in total length and 1 to 6 years old (median = 5 years), while the clams from the southern end were between 9.8 and 15.3 cm (13 cm) and 1 to 6 years old (median = 5 years) (Fig. 3). The majority of the clams were between 13-13.9 cm (22.7% and 36.3% in the north and south, respectively) and 5 years old (34% and 37% in the north and south respectively), suggesting most individuals are able to reproduce before dying. Abundance, total lengths, and ages of the clams during 2022–2023 were not significantly different in the north vs. the south side (t = 0.52, 0.88, and 1.98, P = 0.32, 0.19, and 0.51, respectively; Figs. 3, 4). Total lengths and ages were significantly and positively related to each other on the north and south sides (Fig. 2, r2 = 0.76 and 0.68, P < 0.01), and average growth rates (1.54 ± 0.14 vs. 1.62 ± 0.20 cm per year) were not significantly different between the two sides (Full model, F3,73, P < 0.0001, North vs. South side, t = -0.161, P = 0.872, Interaction with Age, t = 0.194, P = 0.847; Fig. 3). Max lengths and ages were lower during 2022–2023 compared to 1958/59 on the northern side (14.5 vs. 15.1 cm and 6 vs. 7 years), but similar on the southern side (15.3 vs. 15 cm and 6 vs. 6 years) (Fig. 2).

This was the first study of the Pacific razor clam population at Clam Beach in Humboldt, California since the late 1950s that includes length and age. Our focus was to investigate the population of Pacific razor clams with a different monitoring approach from what is typically used to monitor other populations of the same species. While traditional methods, such as sampling live clams, would have provided direct comparisons to Sims’ (1960) data, by counting and collecting empty shells, we were able to estimate the length, age, and growth of the populations in the north and south fishing regions, between which we found no significant differences. While this is not sufficient to predict population size, it does give us an insight into the length, age, and growth rates of individuals in the population in a non-lethal and less cost-prohibitive way (Yap 1977; Berger 2017). If clam shells were collected over multiple years it could also provide inferences about trends in their abundance and mortality rates.

When comparing data from the north vs. the south side of the beach, we observed different patterns in our empty shells data compared to Sim’s (1960) live clam study. In the late 1950s, the abundance, length, and age were higher in the north than on the south side, while at present they are not significantly different. Maximum length and age were slightly higher in the late 1950s than in the present on the north side but not on the south side (Fig. 4). This suggests that habitat conditions on the north side may have diminished since the late 1950s, while they may have stayed the same on the south side. The differences in maximum length and age could be due to changes in the water quality of Strawberry Creek, Patrick Creek, and Mad River, which flow into or near the southern side of Clam Beach (Fig. 1). These streams and rivers had high rates of E. coli and enterococci due to fecal contamination (Corrigan et al. 2021) that caused Clam Beach to receive its seventh failing grade for poor water quality out of the past 11 years in 2020–2021 (Heal the Bay 2021). Our similar south maximum length and age results could therefore be because there has been an increase in particulate organic matter flowing from these streams to the south side of Clam Beach, potentially increasing food availability for clams. However, our results could also be due to differences in methodologies as when collecting empty shells, we are uncertain on where these clams lived, and therefore the shells of clams could have been transported by currents and tides from one side to the other. Future work should focus on how far empty shells can disperse among beaches and sampling with both the present and more traditional methods using live clams to evaluate the effectiveness of the current method.

We could not directly compare our abundance estimate data with Sims (1960) because it is uncertain if the empty shells that we collected originated on the side of the beach (north or south region) where we collected them. However, the fact that we did not observe any clammers during our transects despite the fishery being open after a 5-year closure, and being told anecdotally by known local fishers/harvesters that it has been difficult to collect live clams while fishing recreationally in the last few years, could suggest their abundances have decreased. It is unclear what may be causing this decrease in population size as the water temperature in the surf zone does not seem to have varied during the summer since the 1950s (11.8°C in the 1950s vs. 11.7 ± 1.2 °C in 2019 and 2020; Terhaar 2022). These results suggest more extensive monitoring is necessary, potentially including other environmental variables such as wave height, which has been increasing in the Pacific Northwest (Ruggiero et al. 2010). Wave height is suggested because it can impact, among other things, sediment movement and currents in the surf zone, which can affect larval dispersal and settlement, and adult survival. Furthermore, if the current method were to continue being used, a mark-recapture study of empty clam shells needs to be carried out to determine how far and how quickly they could be dispersed by the coastal ocean.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded with a CSU Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology (COAST) Undergraduate Student Research Support Program and Cal Poly Humboldt Marine & Coastal Science Institute Undergraduate Student Research Award to Gabriel Irribarren. We are also grateful to J. Hodge, an undergraduate at Cal Poly Humboldt, who assisted with fieldwork.

Literature Cited

- Berger, D. 2017. Razor Clams: Buried Treasure of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA, USA.

- Bowen, L., K. L. Counihan, B. Ballachey, H. Coletti, T. Hollmen, B. Pister, and T. L. Wilson. 2020. Monitoring nearshore ecosystem health using Pacific razor clams (Siliqua patula) as an indicator species. PeerJ, 8:e8761. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8761

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). 2020. Pacific razor clam. Marine Species Portal. Available from: https://marinespecies.wildlife.ca.gov/pacific-razor-clam/false/ (Accessed: 20 Feb 2024)

- California Department Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). 2023. Fishing and Hunting Regulations. Available from: https://wildlife.ca.gov/Regulations (Accessed: 10 February 2023)

- Corrigan, J. A., S. R. Butkus, M. E. Ferris, and J. C. Roberts. 2021. Microbial source tracking approach to investigate fecal waste at the Strawberry Creek watershed and Clam Beach, California, USA. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(13):6901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136901

- Heal the Bay. 2021. Beach Report Card & River Report Card 2020–2021. Available from: https://healthebay.org/beachreportcard2021/ (Accessed: 14 October 2023)

- Hiebert, T. C. 2015. Siliqua patula, the flat razor clam. Pages 764–770 in T. C. Hiebert, B. A. Butler, and A. L. Shanks, editors. Oregon Estuarine Invertebrates: Rudys’ Illustrated Guide to Common Species. Third edition. University of Oregon Libraries and Oregon Institute of Marine Biology, Charleston, OR, USA.

- Ruggiero, P., P. D. Komar, and J. C. Allan. 2010. Increasing wave heights and extreme value projections: the wave climate of the U.S. Pacific Northwest. Coastal Engineering 57:539–552.

- Sims, C. W. 1960. A study of the fishery and the population of the Pacific razor clam, Siliqua patula, of Clam Beach, California. Thesis, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA, USA.

- Szarzi, N. J., 1991. Distribution and abundance of the Pacific razor clam, Siliqua patula (Dixon) on the eastside Cook Inlet beaches, Alaska. Dissertation, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK, USA.

- Terhaar, K. B. 2022. A characterization of the sandy beach surf zone fish community and their ecology in northern California and the effects of Marine Protected Areas. Thesis, California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, Arcata, CA, USA.

- Wiyot Tribe. (n.d.). Cultural. Wiyot Tribe. Available from: https://www.wiyot.us/148/Cultural (Accessed: 25 June 2024)

- Weymouth, F. W. 1923. The life-history and growth of the Pismo clam:(Tivela stultorum Mawe). Fish Bulletin No. 7. California Fish and Game Commission, Sacramento, CA, USA.

- Yap, W. G. 1977. Population biology of the Japanese little-neck clam, Tapes philippinarum, in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, Hawaiian Islands. Pacific Science 31(3):223–244.