The San Joaquin Kit Fox: Biology, Ecology, and Conservation of an Endangered Species

BOOK REVIEW

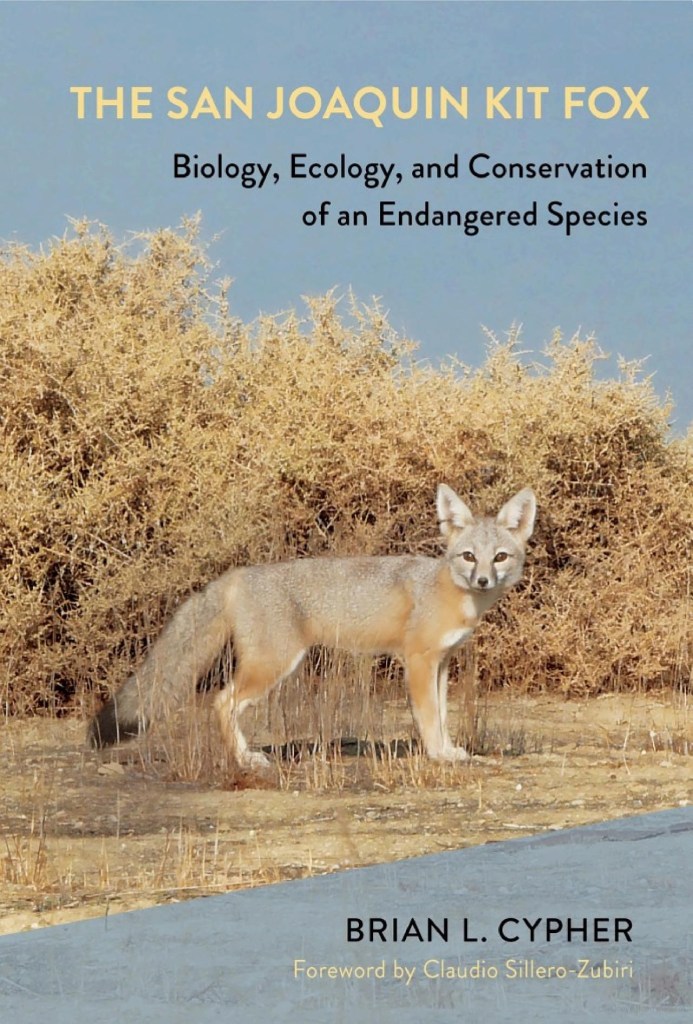

Brian L. Cypher. 2024. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, USA. 222 pages (hardcover). $53.95. ISBN: 978-1-5017-7505-5.

www.doi.org/1.151495/cfwj.110.20

Brian Cypher, research ecologist and carnivore specialist, has produced a much needed and long-awaited book on the San Joaquin kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica), a charismatic carnivore endemic to the San Joaquin Valley. This highly digestible volume ties together decades of research focusing on the San Joaquin kit fox and curious readers will finish the book with a satisfying understanding of this rare critter.

The book is divided into several sections, including an Introduction (Why a Book About the San Joaquin Kit Fox?) and four chapters: (1) “San Joaquin Kit Fox Overview,” (2) “Natural History,” (3) “Contemporary Challenges,” and (4) “Conservation.” Following these chapters include a “Conclusion” section covering The Future of the fox, then an appendix covering the common and scientific names of species mentioned in the text, a Literature Cited section, and an Index. Front matter of the book includes a list of illustrations (60 figures total), a Forward by Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, a Preface, and Acknowledgements.

The first chapter, “San Joaquin kit fox Overview,” is further broken down into several subsections covering topics like general description, adaptations, ecology, status, evolution, and taxonomy. The chapter sets the foundation to familiarize the reader with the San Joaquin kit fox and its place in San Joaquin Valley ecosystem. The San Joaquin kit fox is a subspecies listed as “Endangered” by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1967 (USFWS 1967) and as “Threatened” by the State of California in 1971 (USFWS 1998). The San Joaquin kit fox is isolated from other kit fox subspecies and no genetic exchange currently occurs. In the geologic past, various species of arid-adapted plants and animals spread into the San Joaquin Valley from the Mojave Desert when movement was feasible over the mountain passes between these two regions. Along with the kit fox, other species, such as kangaroo rats, leopard lizards, Opuntia cactus, and antelope squirrels, made the journey and now call the San Joaquin Desert home (Germano et al. 2011). Although likely once occupying a larger portion of the San Joaquin Valley, the kit fox now occurs within three “core” areas and several smaller “satellite” populations with limited connectivity. In this chapter, Cypher also covers how the San Joaquin kit fox differs from other fox species and coyotes (Canis latrans). Misidentifications sometimes occur, and knowing the difference is important (Clark et al. 2007).

The second chapter, “Natural History,” covers a variety of topics, including distribution and habitat, survival, reproduction, population dynamics, foraging, space use, dens, social ecology, and other behaviors. These topics are crucial in understanding the overall species dynamics as they occur on the desert landscape. An interconnecting thread that ties many of these topics together is the “bottom up” ecological principle that binds rainfall, vegetation, and prey populations, such as kangaroo rats. Years with good rainfall and years with drought all influence vegetative growth which in turn influences rodent populations, the main prey for the San Joaquin kit fox. The way that kit foxes respond to these “bottom up” influences may lag and determines if the foxes reproduce or not. Kit fox survivability is deeply tied to the landscape and the interactions between biotic and abiotic factors. The chapter also covers the general behaviors of the fox and how it tackles the desert environment. The kit fox is mainly active at night and stays in dens during the day. These sorts of activities allow the fox to escape high daytime temperatures, a strategy that kangaroo rats and other rodents exhibit as well, which goes hand in hand with the foraging strategy of the kit fox.

The third chapter, “Contemporary Challenges,” includes sections on how kit foxes interface with a variety of landscape changes caused by human activities, such as oil extraction, solar farms, agriculture, roads, urban development, and climate change. These developments on the landscape have different impacts on the kit fox. The foxes seem to persevere within oil fields and solar farms, if there are patches of habitat and a prey base. In some instances, features like solar farms, may benefit foxes more so than other natural lands. Solar farms are surrounded with fencing designed to exclude coyotes and allow foxes to travel through based on the size of the lower wire dimensions. The solar fields support kangaroo rats and other rodents allowing kit foxes to co-occur with solar development and reduce coyote predation. Other development features, such as roads, are not as friendly. Vehicle strikes are a common mortality source. Counterintuitively, some may think urban areas are not compatible with kit foxes, but the City of Bakersfield has had kit fox populations for decades, and they seem to be doing rather well. The City is not necessarily designed to be kit fox friendly, but there are enough open space features to allow kit foxes to co-exist with the urban interface. Railroad and canal corridors, flood control basins, school yards, and golf courses are all areas where kit foxes can maintain dens and raise young. Interactions with the public are generally positive, and the kit fox has become a wildlife ambassador for its conservation and the appreciation of wildlife in general (Bjurlin and Cypher 2005).

The fourth and final chapter, “Conservation,” is a must read to gain a better understanding of the history of research and conservation efforts, biopolitics and attitudes, and research and conservation needs. It is well written and a great summary that I have not seen elsewhere. The history section starts from when Joseph Grinnell and colleagues first recognized the San Joaquin kit fox as a distinct subspecies and provided the initial life history description for the fox (Grinnell et al. 1937). Cypher continues in the history section covering various ecological studies that occurred over the years and his personal involvement as a researcher in the 1990s within the oil preserves in Kern County, which was eventually summarized in a monograph (Cypher et al. 2000). Conservation efforts over the past several decades resulted in lands being set aside within core areas and the eventual publication of the Recovery Plan of Upland Species by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS 1998). In this Recovery Plan, the kit fox was designated as an “umbrella species” so that conservation habitat set aside for the kit fox also benefits other species that also occur on these preserved habitats. The Recovery Plan was the one of the first to propose conservation measures and recovery efforts on the community level, rather than species by species. The Recovery Plan covers, including the kit fox, 34 species of plants and animals, all imperiled in one form or another, within the San Joaquin Desert (USFWS 1998). Cypher argues that although the Recovery Plan has served as the primary guide for kit fox conservation, it has become increasingly outdated as new conservation tasks are being identified. Decades of research topics have been explored and aided in the overall ecological understanding of the kit fox, but further data gaps have been identified. Additional conservation habitat still needs to be set aside for the fox and other arid-adapted species within the San Joaquin Valley. Overall, there’s been a net loss of habitat over the years, but with climate change, suitable habitat can be potentially created as habitat attributes shift over time. Retired farmlands and oil fields can be converted to suitable habitat, and in areas north and east of the current range, once modeled as low quality or suboptimal, can become suitable with climate change-induced vegetative shifts. The Recovery Plan’s ultimate goal is to provide a path to delist or downlist the species covered in the plan. For that to happen, stable populations of the listed species will need to be permanently conserved in specific areas. Cypher states that there is no evidence that this approach will prevent the species from going extinct, and the authors of the plan realized this shortcoming. As a result, the authors called for conducting a Population Viability Analysis (PVA), an important tool in conservation and recovery efforts, but are only as good as the data available to input into the model. Unfortunately, a PVA has not been initiated for the San Joaquin kit fox and should be a future conservation priority.

In the “Conclusion” section, Cypher addresses the future of the San Joaquin kit fox. Essentially, the future is uncertain. Continued habitat loss and landscape fragmentation still occur. The human population within the State of California continues to grow, and the demands on the land and other resources are substantial. Disease is a concerning factor, as evidenced by the mange issue within the urban Bakersfield kit fox population. Climate change is of further concern, as is the possibility of some unforeseen large-scale catastrophic event. The approaches outlined in Butterfield et al. (2021) in rewilding agricultural landscapes may help, and these actions should start happening sooner rather than later.

Cypher ends his book on a positive note (p. 193): “With their adaptability and mobility, kit foxes stand a better chance of hanging on compared with some other species. The loss of this San Joaquin Valley native would not only be a sad and depressing outcome, but it would also indicate poor prospects for other less adaptable and less mobile co-occurring species, and for arid ecosystems in the San Joaquin Valley in general. However, I am optimistically hopeful, hopefully not naively so, that people will continue to catch glimpses of this charismatic species for generations to come.”

Cypher’s book is a pleasure to read and provides a succinct treatment of the accumulative knowledge of one of the animals that I hold dear. The book welcomes readers from varied backgrounds and walks of life, including naturalists, students, landowners and stewards, and wildlife professionals alike. I highly recommend The San Joaquin Kit Fox to all those concerned about the future of our wildlife friends, especially the San Joaquin kit fox.

Howard O. Clark, Jr.

Colibri Ecological Consulting, LLC, 9493 N Fort Washington Road, Suite 108 Fresno, CA 93730, USA https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8384-2163

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8384-2163

Acknowledgments

I thank S. I. Hagen for providing numerous improvements to the manuscript.

Literature Cited

- Bjurlin, C. D., and B. L. Cypher. 2005. Encounter frequency with the urbanized San Joaquin kit fox correlates with public beliefs and attitudes toward the species. Endangered Species Update 22:107–115.

- Butterfield, H. S., T. R. Kelsey, and A. K. Hart. 2021. Rewilding Agricultural Landscapes: A California Study in Rebalancing the Needs of People and Nature. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Clark, H.O., Jr., D. P. Newman, and S. I. Hagen. 2007. Analysis of San Joaquin kit fox element data with the California Diversity Database: A case for data reliability. Transactions of the Western Section of the Wildlife Society 43:37–42.

- Cypher, B. L., G. D. Warrick, M. R. M. Otten, T. P. O’Farrell, W. H. Berry, C. E. Harris, T. T. Kato, P. M. McCue, J. H. Scrivner, and B. W. Zoellick. 2000. Population dynamics of San Joaquin kit foxes at the Naval Petroleum Reserves in California. Wildlife Monographs 145:1–43.

- Germano, D. J., G. B. Rathbun, L. R. Saslaw, B. L. Cypher, E. A. Cypher, and L. M. Vredenburgh. 2011. The San Joaquin Desert of California: ecologically misunderstood and overlooked. Natural Areas Journal 31:138–147.

- Grinnell, J., J. S. Dixon, and J. M. Linsdale. 1937. Fur-bearing Mammals of California: Their Natural History, Systematic Status, and Relations to Man. Volume 2. University of California, Berkeley, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, USA.

- U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 1967. Native fish and wildlife. Endangered species. Federal Register 32:4001.

- U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 1998. Recovery plan for upland species of the San Joaquin Valley, California. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR, USA.