First record of Lepidurus lemmoni (Holmes 1894) (Crustacea: Notostraca) in California’s Central Valley

RESEARCH NOTE

Sean M. O’Brien* and Brent Helm

Westervelt Ecological Services, 3636 American River Drive, Sacrament, CA 95864, USA https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-5161-7049 (SMO)

https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-5161-7049 (SMO)

*Corresponding Author: seanobrien1342@gmail.com

Published 23 March 2025 • doi.org/10.51492/cfwj.111.1

Key words: largebranchiopod, Lepidurus packardi, playa, San Joaquin, tadpole shrimp, Tulare Basin, vernal pool

| Citation: O’Brien, S. M., and B. Helm. 2025. First record of Lepidurus lemmoni (Holmes 1894) (Crustacea: Notostraca) in California’s Central Valley. California Fish and Wildlife Journal 111:e1. |

| Editor: Raffica LaRosa, Habitat Conservation Planning Branch |

| Submitted: 16 October 2024; Accepted: 25 November 2024 |

| Copyright: ©2025, O’Brien and Helm. This is an open access article and is considered public domain. Users have the right to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles in this journal, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, provided the authors and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife are acknowledged. |

| Competing Interests: The authors have not declared any competing interests. |

Tadpole shrimp (Order Notostraca) are an order of branchiopod crustaceans and one of the three large branchiopods (fairy shrimp, tadpole shrimp, and clam shrimp) (Brendonck et al. 2008). Two extant genera occur worldwide, Triops and Lepidurus. These animals occur in seasonally astatic aquatic habitats (Brendonck et al. 2022). Rogers (2001) and Helm and Noyes (2016) reported only one Lepidurus species from the California Great Central Valley, USA, the federally endangered vernal pool tadpole shrimp (L. packardi Simon, 1886), which occurs in vernal pool-type astatic wetlands. However, we observed L. lemmoni Holmes, 1894, in the southern portion of the Central Valley in 2019 in alkaline playa-type astatic wetlands. Lepidurus lemmoni has been referred to as the “alkali tadpole shrimp” (Helm 1998), “Lemmon’s tadpole shrimp” (Helm and Noyes 2016), and “Lynch tadpole shrimp” (NatureServe 2024).

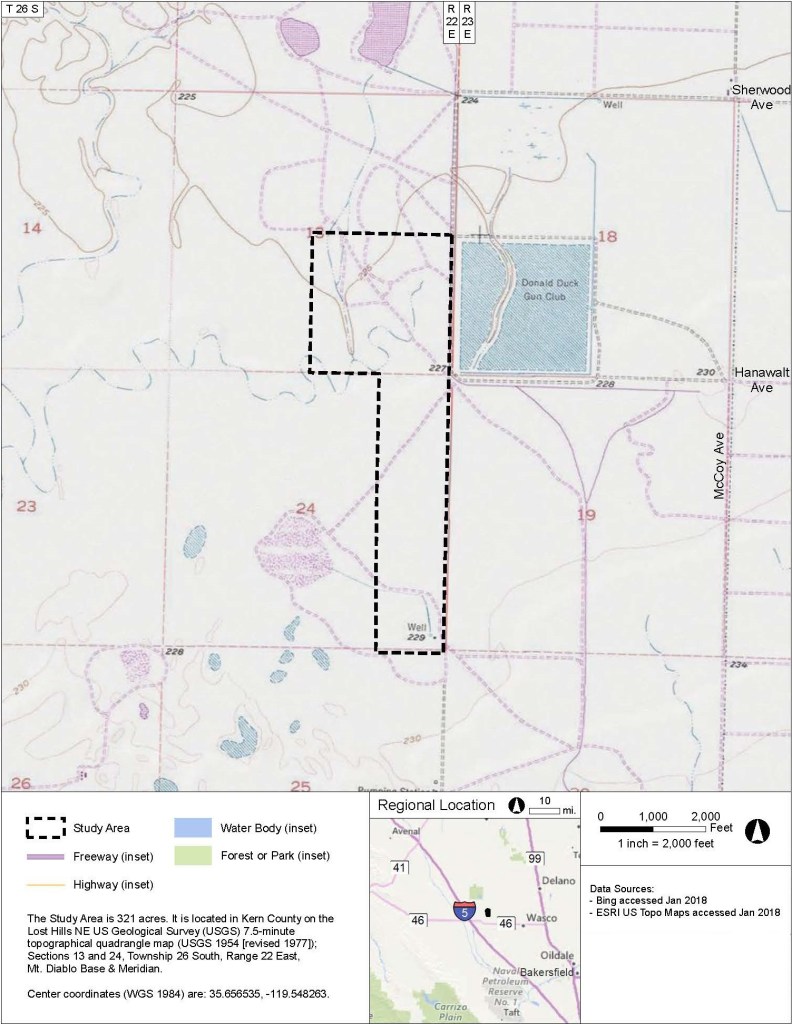

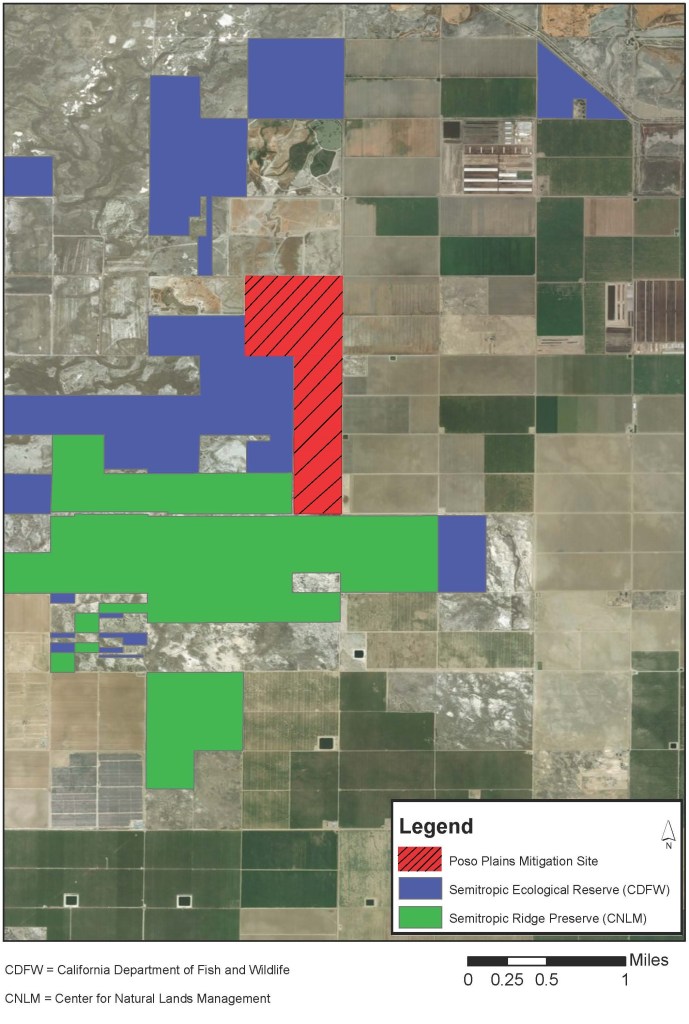

We captured L. lemmoni from several playa-type pools while we conducted wet season surveys for federally listed vernal pool crustaceans at Poso Plains Mitigation Site, owned and managed by Westervelt Ecological Services. The site covers nearly 130 ha east of Interstate 5 and north of State Highway 46, roughly 6 km south by southeast from the southeast corner of the Kern National Wildlife Refuge, Kern County, CA (Fig. 1). Specifically, the site occurs east of Corcoran Road, south of Sherwood Avenue Extension, and west of Gun Club Road (lat. 35.659 o lon. -119.546 o decimal degrees, World Geodetic System 1984). The site lies along the southern edge of the historic Tulare Lake shoreline, at elevations of 67.7-69.8 m above mean sea level (Fig. 2). The site occurs within the Garces Silt Loam soil mapping unit, which consists of saline alkali soils associated with the basin rim landform (Natural Resource Conservation Service 2024). We also observed Lepidurus lemmoni on the adjacent Semitropic Ecological Reserve, owned and managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), to the west of Poso Plains Mitigation Site (Fig. 3). We hypothesize that our new-found L. lemmoni occurrences represent a historical distribution of the species within the Central Valley that was previously undiscovered.

We observed L. lemmoni on 26 March 2019 in three alkaline playa pools (Fig. 4). Co-occurring species included alkali fairy shrimp (Branchinecta mackini Dexter, 1956), versatile fairy shrimp (B. lindahli Packard, 1883), and tadpoles of the western spadefoot (Spea hammondii Baird, 1859). The L. lemmoni specimens were identified using Linder (1952), Pennak (1978), and Rogers (2001). For example, the nuchal organ arrangement was characteristic of L. lemmoni (Fig. 5), occurring behind a line drawn between the posterior apices of the eyes, unlike the nuchal organ of L. packardi which is intersected by such a drawn line (Rogers 2001). Additionally, the specimen was “shining yellow or grayish silver to light green,” which is characteristic (Rogers 2001).

Three Lepidurus species have been reported from California (Rogers 2001; Helm and Noyes 2016). Only Lepidurus packardi has previously been reported from the California Central Valley (Rogers 2001; Helm and Noyes 2016). Lepidurus packardi was listed as threatened in 1994 under the federal Endangered Species Act primarily due to destruction of its vernal pool habitats (Helm 1998), of which over 90% have been destroyed (Holland 2009; Witham 2021). Lepidurus packardi is reported from the Central Valley from Shasta County to Tulare/Kings County (Helm 1998; Rogers 2001; Helm and Noyes 2016). The southernmost occurrence of L. packardi is within alkaline pools at Cross Creek Preserve in northern Kings/Tulare County located ~80 km north of the newfound L. lemmoni occurrence.

Lepidurus lemmoni typically occurs in medium to large, hard, alkali desert playa-type astatic pools with pH values ranging from 8.2 to 11.3, although is occasionally observed in small turbid alkaline pools (Rogers 2001). The species is reported from Canada, Montana, Wyoming, Washington, Oregon, Nevada, California, Arizona, and Baja California Norte (Lynch 1966; Rogers 2001; Brostoff et al. 2010; Hossack et al. 2010; Rogers and Hill 2013). Lepidurus lemmoni is a common occurrence within California large alkali playas in the Great Basin (Lassen, Modoc, Siskiyou counties) and Mojave Desert (southeast Kern County and northern Los Angeles County). The species is not known from California’s Central Valley (Rogers 2001; iNaturalist 2024).

Our new locality is ~162 km northwest of the nearest previously known record of the species located in the Mojave Desert west of Rogers Dry Lake (iNaturalist 2024) (Fig. 6). Given that large branchiopod eggs can survive ingestion by ducks and shorebirds (Rogers 2014), it is plausible that the Central Valley population was historically colonized via migrating waterfowl and other water birds. While great distance and a major geographic barrier separates the two localities, their ecology and species assemblages are not dissimilar.

The climatic conditions of the new locality and nearest Mojave Desert locality are cold semi-arid/desert (BSk/BWk, Kottek et al. 2006; Germano et al. 2011) differing from the majority of the Central Valley, which is warm-summer Mediterranean (CSa, Kottek et al. 2006). The new locality and nearest Mojave Desert locality receive approximately 18 cm (7 in) of annual rainfall, lower than more northern portions of the Central Valley which receive between 33 cm (13 in) (Fresno) and 89 cm (35 in) (Redding) of annual rainfall (U.S. Climate Data 2024). Substrate pH in the Tulare Basin pools ranged from 9.23 to 10.52, which is within the range reported for this species (8.2 to 11.3) (Rogers 2001) and close to that of substrates near the nearest Mojave Desert locality (pH 9) (Brostoff et al. 2010). The Tulare Basin pools supporting L. lemmoni resemble Mojave Desert playa-type pools (large and flat-bottomed) (Germano et al. 2011). Tulare Basin playa-type pools and Mojave Desert playas share a similar hydrologic regime, in which they may remain dry for several years (Brostoff et al. 2010; authors, pers. obs.), unlike more northern Central Valley vernal pools which inundate more frequently.

The climate, hydrology, and soils result in similar vegetation types for both locations (Germano et al. 2011). The Tulare Basin playa-type pools are dominated by sparse salt-tolerant, aquatic plant species (<5% aerial cover) usually along their edges (Fig. 4). Typical plants include alkali barley (Hordeum depressum), alkali popcorn flower (Plagiobothrys leptocladus), alkali peppergrass (Lepidium dictyotum), alkali-weed (Cressa truxillensis), bush seepweed (Suaeda nigra), California alkali grass (Pucchella simplex), iodine bush (Allenrolfea occidentalis), saltbush species (Atriplex spp.), and saltgrass (Distichlis spicata). Similar taxa dominate Mojave Desert playa pools, which include the same species, with the addition of woody subshrubs – black greasewood (Sarcobatus vermicularis), Mojave red sage (Neokochia californica), and Boraxweed (Nitrophila occidentalis)(Brostoff et al. 2010; Germano et al. 2011).

The Tulare Basin and the Mojave Desert pools support similar assemblages of aquatic invertebrates, including alkali fairy shrimp and versatile fairy shrimp. Lepidurus lemmoni is known to prey upon fairy shrimp in Mojave Desert pools (Lynch 1966; Brostoff et al. 2010), and this is likely the case in Tulare Basin pools. Bothalkali fairy shrimp and versatile fairy shrimp are known to occur in alkali pools throughout the Mojave Desert, Great Basin, and the Central Valley (primarily the San Joaquin Valley and western side of the Sacramento Valley) (Eriksen and Belk 1999). However, Tulare Basin pools lacked other large branchiopods typical of Mojave Desert pools, including giant fairy shrimp (Branchinecta gigas Lynch, 1937), desert tadpole shrimp (Triops sp.), and clam shrimp (Cyzicus sp. and Eocyzicus digueti Richards, 1895).

The historical distribution of L. lemmoni in the Central Valley is difficult to ascertain because the majority of historical habitat has been destroyed and converted to agriculture (Preston 1981). Remnant alkali pools in the Tulare Basin are concentrated between 0 to 25 km south of the southern edge of the historic Tulare Lake (Mendell et al. 1874; Baker 1876), east of Interstate 5 and north of State Highway 46. These lands include federal and state preserves (e.g., U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Kern National Wildlife Refuge and CDFW’s Semitropic Ecological Reserve), mitigation lands (Westervelt Ecological Service’s Poso Plains, Alkali Flats, CD Hillman, and Antelope Plains Mitigation Sites and Center for Natural Lands Management’s Semitropic Ridge Preserve), and private property (including several duck hunting clubs) (Fig. 3).

If L. lemmoni co-occurred in areas with other federally listed large branchiopods, it would have likely been detected in surveys for those species. Lepidurus lemmoni likely does not occur north of the Pixley National Wildlife Refuge, the southernmost extent of the federally threatened vernal pool fairy shrimp (Branchinecta lynchi; Eng et al. 1990), which occurs 32 km northeast of our new records. Areas between Poso Plains Mitigation Site and Pixley National Wildlife Refuge, such as CDFW’s Allensworth Ecological Reserve, should conduct focused surveys for L. lemmoni.

The southernmost extent of L. lemmoni is even more difficult to speculate due to the minimal remaining suitable habitat and limited survey data. Private and public lands in this region, such as CDFW’s Buttonwillow Ecological Reserve, Westervelt Ecological Services’ proposed Buttonwillow Conservation Bank, and Jumper Conservation Bank Preserve, may require L. lemmoni focused surveys.

Alkali playa-type pool habitats in the Tulare Basin have had infrequent surveys due to the absence of federally-listed branchiopod species. Additionally, the Tulare Basin lacks consistent annual rainfall, and as such, the pools do not inundate each year to allow consistent surveys. Furthermore, when the saline/alkaline clay soils become wet (during the narrow survey window) it is very difficult to traverse. Lastly, private landowners in this area are particularly resistant to biological surveys.

An alternative hypothesis is that this species occurrence represents a more recent natural or anthropogenic range expansion. The area in which this species was found has a rich history of waterfowl hunting and farming. Therefore, our new-found occurrence may be the result of a recent bird translocation. Similarly, L. lemmoni eggs could have been unintentionally imported from soil adhering to farming or hunting equipment (e.g., waders, decoys, blinds). Future surveys targeting L. lemmoni in the surrounding region may provide support for whether this is a recent or historical range expansion.

The order Notostraca is known to exhibit extreme morphological plasticity, so it is also possible that the newfound specimens are not L. lemmoni, but are new, cryptic species that diverged upon geographic isolation (King and Hanner 1998; Rogers 2001; Adamowicz and Purvis 2005; Brendonck et al. 2022). Exploration of this tertiary hypothesis would require additional morphological and genetic analysis.

The discovery of a new record (or possibly new or cryptic species) previously unreported from the Central Valley implies that Tulare Basin pools provide habitat for rare species at risk and should be protected (Preston 1981). Furthermore, alkali pools within this region should receive more intensive and widespread survey attention, especially for large branchiopods.

Acknowledgments

We are appreciative of F. Cannizzo for her assistance in collecting field data and of Westervelt Ecological Services and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife for land access. We are thankful to Dr. C. Rogers, Dr. J. Kneitel, R. Lopez, F. Cannizzo, I. Parr, and four anonymous reviewers for their insightful reviews.

Ethics Statement

This project was authorized by USFWS under permit number TE 795930.10.2.

Literature Cited

- Adamowicz, S. J., and A. Purvis. 2005. How many branchiopod crustacean species are there? Quantifying the components of underestimation. Global Ecology and Biogeography 14(5):455-468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-822x.2005.00164.x

- Baker, P. Y. 1876. Map of Tulare County, California. Available from: https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~205302~3002357:Map-Of-Tulare-County-California- (Accessed 9 October 2024)

- Brendonck, L., D. C. Rogers, J. Olesen, S. Weeks, and W. R. Hoeh. 2008. Global diversity of large branchiopods (Crustacea: Branchiopoda) in freshwater. Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment 595:167-176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9119-9

- Brendonck, L., D. C. Rogers, B. Vanschoenwinkel, and T. Pinceel. 2022. Large branchiopods. Pages 273–305 in T. Dalu and R. J. Wasserman, editors. Fundamentals of Tropical Freshwater Wetlands: From Ecology to Conservation Management. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2019-0-04375-0

- Brostoff, W. N., J. G. Holmquist, J. Schmidt-Gengenbach, and P. V. Zimba, 2010. Fairy, tadpole, and clam shrimps (Branchiopoda) in seasonally inundated clay pans in the western Mojave Desert and effect on primary producers. Saline Systems 6:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1448-6-11

- Eriksen, C. H., and D. Belk. 1999. Fairy Shrimps of California’s Puddles, Pools, and Playas. Mad River Press, Inc., Eureka, CA, USA.

- Germano, D. J., G. B. Rathbun, L. R. Saslaw, B. L. Cypher, E. A. Cypher, and L. M. Vredenburgh. 2011. The San Joaquin Desert of California: ecologically misunderstood and overlooked. Natural Areas Journal 31(2):138–147. https://doi.org/10.3375/043.031.0206

- Helm, B. P. 1998. Biogeography of eight large branchiopods endemic to California. Pages 124–139 in C. W. Witham, E. T. Bauder, D. Belk, W. R. Ferren, Jr., an dR. Ornduff, editors. Ecology, Conservation, and Management of Vernal Pool Ecosystems: Proceedings from a 1996 Conference. California Native Plant Society, Sacramento, CA, USA.

- Helm, B. P., and M. L. Noyes. 2016. California large branchiopod occurrences: a comparison of method detection rates. Pages 31–56 in Vernal Pools in Changing Landscapes: Studies from the Herbarium, Number 18. California State University, Chico, CA, USA.

- Holland, R. F. 2009. California’s Great Valley vernal pool habitat status and loss: revised 2005. Prepared for Placer Land Trust, Auburn, CA, USA. Available from: https://www.placerlandtrust.org/uploads/documents/Vernal%20Pool%20Studies%20Report/Great%20Valley%20Vernal%20Pool%20Distribution_Final.pdf (Accessed 9 October 2024)

- Holmes, S. J. 1894. Notes on West American Crustacea. Occasional Papers of the California Academy of Sciences 2:565–589.

- Hossack, B. R., R. L. Newell, and D. C. Rogers. 2010. Branchiopods (Anostraca, Notostraca) from protected areas of western Montana. Northwest Science 84(1):52–59. https://doi.org/10.3955/046.084.0106

- iNaturalist. 2024. Lynch tadpole shrimp (Lepidurus lemmoni). Available from: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/223248-Lepidurus-lemmoni (Accessed 9 October 2024)

- King, J. L., and R. Hanner. 1998. Cryptic species in a “living fossil” lineage: Taxonomic and phylogenetic relationships within the genus Lepidurus (Crustacea: Notostraca) in North America. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 10(1):23–36. https://doi.org/10.1006/mpev.1997.0470

- Kottek, M., J. Grieser, C. Beck, B. Rudolf, and F. Rubel. 2006. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meterologische Zeitschrift 15(3):259–263. https://doi.org/10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130

- Linder, F. 1952. Contributions to the morphology and taxonmy of the Branchiopoda Notostraca, with special reference to North American species. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 102(3291):1–69.

- Lynch, J. E. 1966. Lepidurus lemmoni Holmes: a redescription with notes on variation and distribution. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 85:181–192. https://doi.org/10.2307/3224628

- Mendell, G. H., G. Davidson, and B. S. Alexander. 1874. Report of the Board of Commissioners on the Irrigation of the San Joaquin, Tulare, and Sacramento Valleys of the State of California. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., USA. https://timelessmoon.getarchive.net/amp/media/tulare-lake-1874-1de9dd

- NatureServe. 2024. Lynch tadpole shrimp (Lepidurus lemmoni). Available from: https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.111907/Lepidurus_lemmoni (Accessed 12 June 2024)

- Natural Resource Conservation Service. 2024. Web Soil Survey. Available from: https://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/ (Accessed 9 October 2024)

- Pennak, R. W. 1978. Fresh-water Invertebrates of the United States. 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1980.25.2.0383a

- Preston, W. L. 1981. Vanishing Landscapes: Land and Life in the Tulare Lake Basin. University of California Press, Berkley and Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- Rogers, D. C. 2001. Revision of the nearctic Lepidurus (Notostraca). Journal of Crustacean Biology 21(4):991–1006. https://doi.org/10.1163/20021975-99990192

- Rogers, D. C., and M. A. Hill. 2013. Annotated checklist of the large branchiopod crustaceans of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, USA, with the “rediscovery” of a new species of Branchinecta (Anostraca: Branchinectidae). Zootaxa 3694:249–261. https://doi.org/10.11646/ZOOTAXA.3694.3.5

- Rogers, D. C. 2014. Larger hatching fractions in avian dispersed anostracan eggs (Branchiopoda). Journal of Crustacean Biology 34:135–143. https://doi.org/10.1163/1937240X-00002220

- U.S. Climate Data. 2024. Version 3.0 by US Climate Data. Available from: https://www.usclimatedata.com/ (Accessed 9 October 2024)

- Witham, C. W. 2021. Changes in the distribution of Great Valley vernal pool habitats from 2005 to 2018. Report prepared for the San Francisco Estuary Institute/Aquatic Science Center in Richmond, California under U.S. EPA Region-9 Wetland Program Development Grant CD_99T93601, Sacramento, CA, USA.