Ceratonova shasta infection in Sacramento River Chinook salmon

FULL RESEARCH ARTICLE

John Scott Foott*

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Southwest Region, California-Nevada Fish Health Center, 24411 Coleman Hatchery Road, Anderson, CA 96007, USA https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0892-6425

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0892-6425

*Corresponding Author: jsfoott@gmail.com

Published 21 May 2025 • doi.org/10.51492/cfwj.111.7

Abstract

Field surveys and sentinel studies were conducted with juvenile Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in the Sacramento River between 2012 and 2022. Both Ceratonova shasta and Parvicapsula minibicornis were common myxozoan parasites of both juvenile and adult Chinook salmon. C. shasta infection was found to be associated with morbidity and clinical disease among sampled juvenile salmon in multiple years. This finding demonstrates that disease is another adverse survival factor for juvenile salmon in the Sacramento River. In 2016 and 2018, river water was assayed for C. shasta spore concentration with peak values occurring near Red Bluff Diversion Dam. In some years, C. shasta may reduce juvenile salmon survival. Monitoring water-borne spore stages and salmon infection would inform how flow management influences the parasite lifecycle in the Sacramento River.

Key words: Ceratonova shasta, Chinook salmon, fish disease, Parvicapsula minibicornis, Sacramento River

Introduction

Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) have declined significantly in California’s Central Valley over the last several decades (Yoshiyama et al. 2001). The Central Valley is unique on the Pacific coast in having four separate Chinook salmon runs: fall (California Species of Special Concern [SSC]), late-fall (SSC), spring (federally and California Endangered Species Act [CESA]-listed as threatened), and winter (federally endangered). Varying degrees of hatchery production support all the Central Valley runs. The decline of Central Valley Chinook salmon has been ascribed to many factors: overfishing, non-endemic fish predation, blockage, and degradation of streams by mining activities, reduction of salmon habitat and stream flow by dams and water diversions, hatchery interactions with natural stocks, and disease (Yoshiyama et al. 2001; Sturrock et al. 2019; Lehman et al. 2020).

Ceratonova (syn. Ceratomyxa, Noble 1950) shasta (Atkinson et al. 2014) infects freshwater salmonid fishes and is enzootic to anadromous fish tributaries of the Pacific Northwest of the USA, including the Sacramento River (Hendrickson et al. 1989). Infection by C. shasta often results in enteronecrosis and anemia in juvenile salmon. This disease is a significant mortality factor for juvenile Chinook salmon in the Klamath and Feather Rivers (Foott et al. 2023; Stocking et al. 2006; Fujiwara et al. 2011; Hallett et al. 2012). C. shasta has a complex life cycle, involving an invertebrate polychaete host (Manayunkia occidentalis)as well as the vertebrate salmon host (Atkinson et al. 2020; Bartholomew et al. 1997). Infected polychaetes release actinospores into the water where they attach to the salmon’s gill epithelium, invade into the blood, replicate, and later migrate to the intestinal tract for further multiplication and sporogony (Bjork and Bartholomew 2010). Depending on actinospore genotype and density, innate host resistance, and water temperature, infected juvenile fish can develop varying degrees of enteritis and associated anemia (Udey et al. 1975; Foott et al. 2004; Bjork and Bartholomew 2009; Ray et al. 2010; Hallett et al. 2012). After approximately two-weeks post-infection, the parasite can form the myxospore stage that is typically released after the fish dies. If the myxospore is ingested by the filter-feeding polychaete the parasite completes its life cycle after invading the worm’s gut epithelium (Meaders and Hendrickson 2009).

In the Klamath River, M. occidentalis has been observed to inhabit tubes constructed of fine sediment and mucus in a variety of lotic environments with highest densities found in low velocity areas (Stocking and Bartholomew 2007). M. occidentalis is reported to have an annual reproduction cycle (Willson et al. 2010). The myxosporean, Parvicapsula minibicornis, shares the same hosts and range as C. shasta (Bartholomew et al. 2006). It has a tropism for the kidney nephron and can induce glomerulonephritis in the salmon host. It is often a co-infection with C. shasta with 30–52% prevalence of infection in juvenile Feather River salmon (Foott et al. 2023). While glomerulonephritis is an additive stressor, hemorrhagic enteronecrosis associated with C. shasta is the primary cause of mortality in the co-infected salmon. There is limited information on disease effects on Sacramento River salmon survival. This article describes the prevalence of infection and disease severity due to C. shasta infection in juvenile Sacramento River Chinook, as well as the spatial and temporal patterns of the waterborne spore stages of C. shasta.

Methods

Study Area

We collected fish and water, as well as deploying sentinel groups, from Redding to Knight’s Landing in northern California (Fig. 1). Our fish collection sites were at ongoing trapping locations. We selected water and sentinel sites for public access and geographic distribution.

Histology and Microbiology

We fixed kidney, gill, and gastrointestinal tract, processed the tissues for 5 μm paraffin sections and stained them with hematoxylin and eosin (Humason 1979). We processed fry, smaller than 50 mm, as sagittal sections. Kidney and intestine sample number can differ as insufficient tissue occurred in some sagittal sections. We rated each fish for Ceratonova shasta (CS) and Parvicapsula minibicornis (PM) infection severity. Histological rankings of ‘disease’ were based on the presence of multifocal lesions associated with the parasite infection (CS2 rating of intestine = lamina propria hyperplasia, necrotic epithelium and or sloughing, necrotic muscularis; and PM2 rating of kidney = interstitial hyperplasia, necrotic interstitium or tubules, interstitial granuloma, glomerulonephritis, and protein casts within the glomeruli or tubules). The CS1 and PM1 ratings required the presence of the parasite in the respective tissue but with minimal inflammatory changes. Histological analysis is less sensitive than molecular methods in detecting asymptomatic infections. We examined adult Chinook by histology and QPCR in 1995–2022. In our 2013 and 2014 juvenile salmon surveys, anterior kidney was aseptically collected for bacterial culture (brain heart infusion agar at 22⁰ C incubation), viral testing (inoculation onto EPC and CHSE214 cell lines at 15⁰ C), and Renibacterium salmoninarum (direct fluorescent antibody method) (USFWS and AFS-FHS 2014). We classified gram-negative, motile, no diffusible pigment, oxidase positive bacteria as motile Aeromonas sp./Pseudomonas sp. (AP) (Roberts 1989).

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (QPCR)

We collected intestine (rectum to the junction of small intestine with the pyloric ceca) with separate sterile tools and extracted DNA with an Applied Biosystems MagMax express-96 Magnetic Particle Processer. We used a Ceratonova shasta QPCR assay targeting the 18S ribosomal DNA sequence used to assay DNA extracted from fish tissues. Forward primer (Cs-1034F 5’ CCA GCT TGA GAT TAG CTC GGT AA), reverse primer (Cs-1104R CCC CGG AAC CCG AAA G), and probe (CsProbe-1058T 6FAMCGA GCC AAG TTG GTC TCT CCG TGA AAA C TAMRA) (Hallett et al. 2006). All reactions (30 µL) performed in a 96-well optical reaction plate using 0.9 µM of both primers, 0.25 µM of probe, 15 µL of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, and 5 µL of DNA template. All samples were tested in a single well. We performed the QPCR assays with a 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) with the following cycling conditions: 2 minutes at 50° C and 10 minutes at 95° C, followed by 40 cycles of 95° C for 15 seconds and 60° C for 1 minute. Each assay plate included a standard curve with three concentrations of reference standards (two replicates each) at known DNA copy number and two negative control wells. The C. shasta reference standard curve was obtained using synthesized DNA (gBlock Gene Fragments, Integrated DNA Technology, Coralville Iowa) containing the 18S ribosomal DNA target sequence. Specifically, 1 ng of DNA, corresponding to 6.83×109 copies of C. shasta DNA serially diluted over ten orders of magnitude in Tris-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer. We calculated the cycle threshold (CT) values for each standard concentration using QPCR analysis software (SDS software 7300 SDS v 1.4, Applied Biosystems). Our criteria for a positive test result required samples to produce a change in normalized fluorescent signal (Δ Rn) greater than or equal to 100,000 florescent units and have ≥ 5 copies. Low copy numbers are not reliable given the limitations of the Poisson distribution (Applied Biosystems 2016). Our “disease” threshold of > 3.0 logs of C. shasta DNA was used to segregate data based on the relationship between this value and histological lesion of the intestine (Voss et al. 2020).

Natural Fall-Run Juveniles 2012, 2013, 2016, 2020–2022

We collected juvenile fall-run Chinook salmon from rotary screw traps at Red Bluff Diversion Dam (RB, river kilometer (rkm) 391), and two sites collectively referred to as “Lower Sacramento” (LS); Tisdale Weir (rkm 191.5) and Knight’s Landing (rkm 144.8). Our sampling occurred under California Department of Fish and Wildlife Scientific Collection Permit (SC-4085 and 1836). Euthanized (overdose of MS222) fish were fixed in Davidson’s fixative for histological examination or frozen for QPCR analysis. In late April 2013 (29 April–2 May), we held thirty sentinel Chinook and rainbow trout in cages for three days at LS sites, reared them in the California–Nevada Fish Health Center wet laboratory, and sampled the fish for either histology or QPCR at both 21- and 30-days post-exposure (dpe).

Prognosis of Natural Fall-Run Infection (2014)

We obtained a total of 110 salmon from the LS rotary screw traps between 21 March and 7 April 2014. These dates were selected to maximize collection of larger natural juveniles as late in spring as possible but prior to the arrival of Coleman National Fish Hatchery (NFH) smolts. We transported the salmon to the wet laboratory and held them in 350 L tanks supplied with 18° C (like river temperature) aerated flow-through water and fed the fish frozen tubifex worms. Our intent was to hold fish for 21 days to allow for the development of ceratomyxosis (clinical disease), however, elevated mortality required sampling between nine- and fourteen-days post-collection. Mortality was frozen and those not decomposed assayed for C. shasta DNA by QPCR. Fish rearing and euthanization followed published guidelines (Jenkins et. al. 2014).

Natural Winter-Run Fry from Red Bluff Diversion Dam Trap (2015–2022)

We removed naturally produced winter-run Chinook salmon fry (five to ten fish per sample period) on a weekly or bi-weekly basis during their peak out-migration period (July through December) at Red Bluff Diversion Dam (Poytress and Carillo 2012). We collected Winter-run juveniles under Section 10 (a)(1)(a) permit 1414-2M).

Sentinel Salmon Exposures during Winter-Run Out-Migration

We conducted a sentinel study in September 2015 to examine infectivity of the upper Sacramento River during Winter-run fry out-migration. We exposed Coleman NFH late-fall run Chinook salmon juveniles in the Upper Sacramento River for 5 days in 0.01 m3 cages at Balls Ferry (n = 23, rkm 443) and RB (n = 26, rkm 391) beginning 21 September. Fork length ranged from 90–160 mm. Water temperatures were 15–17⁰ C in-river and 18–19⁰ C in the wet laboratory. We sampled two to five fish per group for histology at 14 dpe with the remainder sampled at 22 dpe. A non-exposed control group also reared at the wet laboratory and sampled as above for histological examination.

In 2016, we exposed sentinel salmon in the upper Sacramento River every four weeks between 25 July and 6 October. We exposed groups of 20 juvenile late-fall run Chinook salmon (mean fork lengths of 74–100 mm) for five days to the Sacramento River at four locations : (1) Posse Grounds (rkm 479), (2) Anderson River Park (rkm 455), (3) Bend Bridge (rkm 415), and (4) Red Bluff Diversion Dam (rkm 391). Rearing temperature for sentinel salmon was 16–17°C in July through 26 September. Due to heating cost limitations, it was lowered to 13–14° C from 26 September to 31 October. We sampled survivors for histology after 24 dpe.

In 2018, we performed four-day sentinel exposures every four weeks between 13 August and 1 November at five locations in the Sacramento River: (1) Reading Island (RI) rkm 441, (2) Red Bluff Diversion Dam (RB) rkm 391, (3) River Road (RV) rkm 312, (4) Highway 162 Bridge (SR) rkm 270, and (5) Tisdale (TS) rkm 191. Sentinel groups consisted of twenty juvenile late-fall run Chinook salmon (mean fork length 84–91 mm). To manage columnaris disease (Flavobacterium columnare), we treatedexposure groups with a 30 min, 2 mg/L nitrofuran bath upon return to the wet laboratory. Columnaris in several sentinel groups was treated with additional nitrofuran baths and tetracycline top-coated feed (0.08 mg/g fish). After 19 to 23 dpe we sampled survivors for histology.

C. shasta Spore Concentration in River Water Samples

We removed four 1-L samples from a 19-L bucket of water collected in a zone of flowing water. We held the samples on ice and filtered them within five hours of collection. We filtered the samples using a vacuum apparatus (Millipore vacuum pump, flask, funnel, and filter holder with MF-Millipore cellulose 47 mm diameter, 5 µm pore filters). We rinsed both the sample bottle and filter assembly with distilled water into the filter. We folded the filter with forceps and placed it into a labeled two mL microfuge tube. Filters were stored at –20° C until shipment on dry ice to the Bartholomew Laboratory at Oregon State University for extraction and QPCR analysis (Hallett and Bartholomew 2006, as modified in Hallett et al. 2012). We wiped both the filter assembly and forceps with DNA away (Molecular BioProducts, San Diego), and rinsed them with distilled water before filtering samples from a new site. Inhibition was assessed for each sample using an internal positive control (Applied Biosystems). Data is reported as mean spores/Liter (majority assumed to be actinospores) from the triplicate samples. Due to high variability in some low concentration samples ( ≤ 1 spore/L), censor rules applied to the data:

- If two of three samples were 0 and the third was > 1.0 = site was 0. (e.g.,0, 0,

4.5) - If two of three samples were > 1.0, and third was 0 it was censored (e.g., 13.2, 6.6,

0) - If a single sample was > 10 spore/L then the other two non-zero samples were averaged for the site mean and the high replicate censored (e.g., 0.5, 0.6,

10.8)

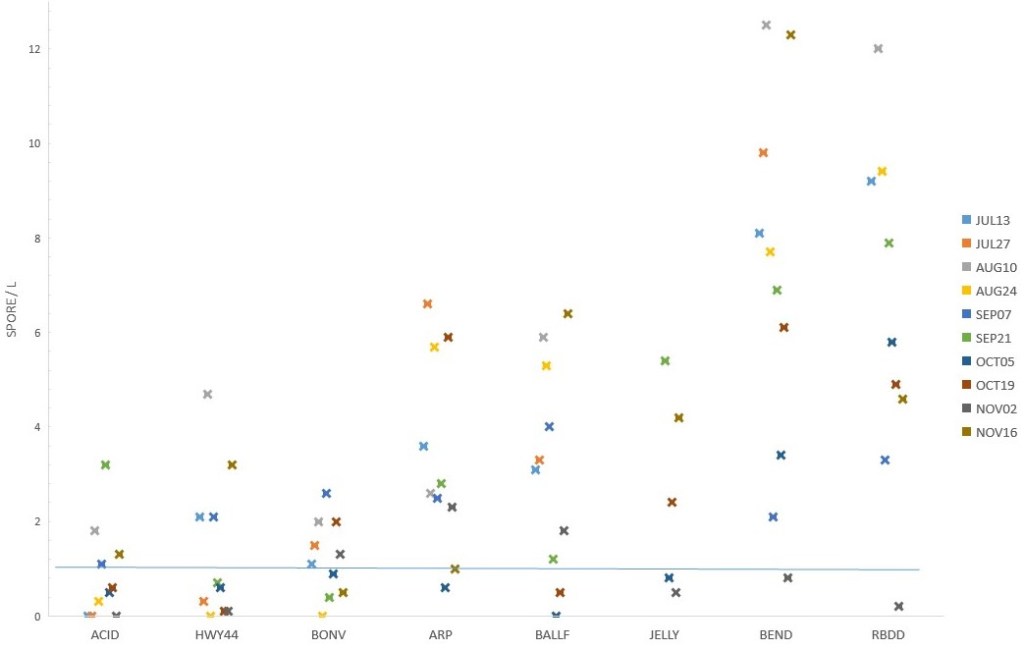

In 2016, our collection sites included: (1) the mouth of the Anderson-Cottonwood Irrigation District (ACID, rkm 478), (2) Highway 44 bridge (HWY44, rkm 477), (3) Bonnyview Bridge (BONV, rkm 470), (4) Anderson River Park (ARP, rkm 455), (5) Balls Ferry bridge ( BALLF, rkm 444), (6) Jelly’s Ferry bridge (JELLY, rkm 430), (7) Bend bridge (BEND, rkm 415), and (8) Red Bluff Diversion Dam (RBDD) (Fig. 1, note sites 1–4 are not individually located on the figure due to scale). In 2018, our collection sites included: (1) Reading Island (R ISL, rkm 441), (2) Red Bluff Diversion Dam (RBDD), (3) River Road (RV RD, rkm 312), (4) Highway 162 bridge (SR162, rkm 270), and (5) Tisdale (TSDL, rkm 192) (Fig. 1).

Results

Adult Chinook Broodstock (1995–2022)

Annual inspection of 15 to 60 fall-run Chinook at Coleman NFH and winter-run Chinook at Livingston Stone NFH included histological examination of intestine and kidney. Prevalence of infection for C. shasta ranged from 24–100% and parasite identity was collaborated by QPCR (Tables S1 and S2). Similarly, the prevalence of P. minibicornis infection ranged from 33–100% and was also collaborated by QPCR (Tables S1 and S2).These adults migrated within the Sacramento River prior to their capture in Battle creek (Coleman NFH) or the Keswick dam trap (Livingston Stone NFH).

Natural Fall-Run Juveniles 2012, 2013, 2016, 2020–2022

We sampled 314 juveniles from the traps with fork lengths ranging from 31–90 mm. There was an increase in fish size with downstream collection locations and later collection dates. No viral cytopathic effect was observed in tissue culture or Renibacterium salmoninarum cells observed in fluorescent antibody-stained imprints from all 221 salmon tested in 2012 (74), 2013 (64) , 2014 (32), or 2016 (51). We isolated Aeromonas /Pseudomonas (AP) bacteria from 10–57% of the 2012–2016 sample groups (n = 158 fish). C. shasta prevalence of infection (CS-POI) showed a spatial pattern with upper river (RB) samples having a much lower CS-POI (3–16%) than LS (35–89%) (Table 1). The prevalence of CS2 rating (disease) was highest in LS samples collected in 2012 and 2021. Similarly, P. minibicornis infection was highest in the LS fish (65–100%) compared to RB (4–35%). Most of these infections were rated PM1 (infected without inflammation). In 2013, sentinel salmon and trout held at LS for three days showed that only salmon became infected (50% CS-POI by QPCR and 66% prevalence of P. minibicornis infection by histology). This data indicates that C. shasta genotype I was the predominate genotype (Atkinson and Bartholomew 2010).

Table 1. Prevalence of Ceratonova shasta (CS) and Parvicapsula minibicornis (PM) infection ranking (parasite observed/total sample, [%]) in juvenile fall-run Chinook histological sections of intestine and kidney, respectively. Histological rankings of ‘clinical disease’ based on the presence of multifocal lesions associated with parasite infection: (CS2) rating of intestine = lamina propria hyperplasia with necrotic epithelium and/or necrotic muscularis and (PM2) rating of kidney = interstitial hyperplasia, necrotic interstitium or tubules, glomerulonephritis, and/or protein casts within the glomeruli or tubules. The #1 rating for these parasite infections required the presence of the parasite in the respective tissue but with minimal inflammatory changes. Prevalence of infection (POI, %) for both parasites is summation of the two rankings. Salmon collected from rotary screw traps at Red Bluff Diversion Dam (RB) and lower Sacramento River sites (LS = Tisdale weir and Knights Landing ) February through April 2012–2022.

| Year | Site | CS1 | CS2 | CS-POI | PM1 | PM2 | PM-POI |

| 2012 | LS | 3/15 (20%) | 6/15 (40%) | 60% | 15/15 (100%) | 0/15 (0%) | 100% |

| 2013 | RB | 1/29 (3%) | 0/29 (0%) | 3% | 7/23 (30%) | 1/23 (4%) | 35% |

| 2013 | LS | 7/20 (35%) | 0/20 (0%) | 35% | 10/20 (50%) | 3/20 (15%) | 65% |

| 2016 | LS | 17/51 (33%) | 1/51 (2%) | 35% | 27/50 (54%) | 0/50 (0%) | 54% |

| 2020 | RB | 3/61 (5%) | 2/61 (3%) | 8% | 6/59 (10%) | 0/59 (0%) | 10% |

| 2020 | LS | 7/8 (88%) | 0/8 (0%) | 88% | 5/8 (63%) | 3/8 (38%) | 100% |

| 2021 | RB | 3/58 (5%) | 5/58 (9%) | 14% | 2/46 (4%) | 0/46 (0%) | 4% |

| 2021 | LS | 7/19 (37%) | 10/19 (53%) | 89% | 10/18 (56%) | 3/18 (38%) | 72% |

| 2022 | RB | 3/44 (7%) | 4/44 (10%) | 16% | 4/35 (11%) | 0/35 (0%) | 11% |

Prognosis of Natural Fall-Run Infection (2014)

We collected 130 juvenile salmon from the LS traps between 21 March and 7 April 7. Post-capture mortality (≤ 14 day) ranged from 18–69% and the rapid onset of mortality for the April 7 group dictated early sampling of the survivors (Table 2). QPCR analysis determined that 91–100% of the mortalities had C. shasta DNA concentrations suggestive of clinical disease. A low percentage of fish showed columnaris lesions or infection by Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (2 of 68 gill sections). P. minibicornis was seen in the kidneys of 91–100% of each collection group (overall prevalence of 97% [68/70 fish]). Glomerulonephritis and interstitial hyperplasia (inflammatory response) occurred in 24% (17/70 fish). C. shasta in the 9–14-day post-capture survivors were seen in 63–96% of the sample groups with 11–25% of the intestines showing clinical signs of disease (Table 2). Combining mortality QPCR and survivor histology results in an overall prevalence of C. shasta infection of 74%.

Table 2. Mortality and C. shasta infection in juvenile fall-run Chinook salmon captured from lower Sacramento R. rotary screw traps in 2014. Collection date, mean (SD) fork length (FL), sample number (Ns), percent mortality in captivity (Mort), C. shasta QPCR positive fish (CS+)/mortality tested, maximum days (Day) held in captivity until survivors sampled for histology, number of survivor rated as CS1 and CS2/total survivor tested, and overall prevalence of C. shasta infection (Cs-POI = mortality QPCR positive + survivor infection/total fry accounted).

| Date | Mean FL (SD) | Ns | Mort | CS+ | Day | CS1 | CS2 | CS-POI |

| 21 March | 45 (8) | 40 | 40% | 16/16 | 14 | 5/24 | 4/24 | 63% |

| 26 March | 54 (9) | 32 | 69% | 20/21 | 13 | 2/9 | 1/ 9 | 78% |

| 3 April | 59 (9) | 25 | 45% | 4/4 | 12 | 11/16 | 4/16 | 96 % |

| 7 April | 56 (11) | 38 | 18% | 7/7 | 9 | 10/19 | 2/19 | 73% |

Natural Winter-Run Fry from Red Bluff Diversion Dam Trap (2015–2022)

Prevalence of C. shasta infection in natural juveniles captured at the RB rotary screw traps ranged from 8–40% (Table 3). Ninety percent or greater of infected salmon were rated as CS1 (infected without associated pathology) indicating early stage infections. P. minibicornis POI tended to be much higher than C. shasta ranging from 10–81% with the majority rated as PM1 infections (Table 3). Lower prevalences occurred in the “below normal” water years of 2016 and 2018 compared to dry or critical years. Mean fork length ranged from 42–61 mm in collection groups.

Table 3. Ceratonova shasta (CS) and Parvicapsula minibicornis (PM) histological infection ranking (fish meeting ranking infection/total sample, [%]) in winter-run Chinook juvenile intestine and kidney histological specimens, respectively. Histological rankings of ‘disease’ were based on the presence of multifocal lesions associated with parasite infection (CS2 and PM2). The #1 rating for both parasites required the presence of the parasite in the respective tissue but with minimal inflammatory changes. Salmon collected from rotary screw traps at Red Bluff Diversion Dam during September through November 2015–2022. Water year hydrological classifications included in parentheses after year—below normal (BN), dry (D), and critical (C).

| Year | CS1 | CS2 | CS-POI | PM1 | PM2 | PM-POI |

| 2015 (C) | 12/80 (15%) | 0/80 (0%) | 12/80 (15%) | 53/74 (72%) | 7/74 (10%) | 60/74 (81%) |

| 2016 (BN) | 5/79 (6%) | 1/79 (1%) | 6/79 (6%) | 6/62 (10%) | 0/62 (0%) | 6/62 (10%) |

| 2018 (BN) | 8/80 (10%) | 0/80 (0%) | 8/80 (10%) | 18/70 (26%) | 0/70 (0%) | 18/70 (26%) |

| 2020 (D) | 6/20 (30%) | 2/20 (10%) | 8/20 (40%) | 8/17 (47%) | 1/17 (6%) | 9/17 (53%) |

| 2021 (C) | 5/20 (25%) | 2/20 (10%) | 7/20 (35%) | 14/20 (70%) | 0/20 (0%) | 14/2 0(70%) |

| 2022 (C) | 5/40 (13%) | 0/40 (0%) | 5/40 (13%) | 14/37 (38%) | 1/37 (3%) | 15/37 (40%) |

Sentinel Salmon Exposures during Winter-Run Out-Migration

In September 2015, sentinel salmon at both locations had a high prevalence of C. shasta infection (Ball Ferry 94% and RBDD 86%) that progressed into disease state (CS2 rating) by 22 dpe (Table 4). Early-stage P. minibicornis infection was also prevalent in the sentinel fish (Ball Ferry 69% and RBDD 50%). Columnaris lesions of the gill and skin were associated with mortality within the first ten dpe (33%, 16/49 fish). No histological samples were taken from mortality due to post-mortem necrosis.

Table 4. Prevalence of Ceratonova shasta (CS) and Parvicapsula minibicornis (PM) histological infection ranking (fish meeting ranking/total sample, [%]) in sentinel Chinook salmon exposed for 5 days at Ball’s Ferry (BALLF) or Red Bluff Diversion Dam (RBDD) in September 2015. Histological rankings of ‘disease’ were based on the presence of multifocal lesions associated with parasite infection (CS2 and PM2). The #1 rating for both parasites required the presence of the parasite in the respective tissue but with minimal inflammatory changes. Control (CONT) fish were not exposed to the river (dpe = days post-exposure).

| dpe | Site | CS1 | CS2 | PM1 | PM2 |

| 14 | CONT | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| 14 | RBDD | 4/4 (100%) | 0/4 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| 14 | BALLF | 4/5 (80%) | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| 22 | CONT | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| 22 | RBDD | 0/11 | 9/11 (80%) | 8/11 (73%) | 0/11 |

| 22 | BALLF | 2/11 (18%) | 9/11 (80%) | 9/11 (82%) | 2/11 (18%) |

We exposed 16 sentinel groups between 25 July and 11 October 2016. Vandalism of exposure cages and a September wet laboratory failure reduced the total sample groups. River temperatures ranged from 11° to 15° C. C. shasta trophozoites were observed in 20% (58/290) of the intestines while P. minibicornis trophozoites were observed in 69% (199/290) of the kidneys (Fig. 2). All infections were rated as #1 (without significant inflammation).There was a general trend of increasing infection prevalence with distance downriver. The upstream Posse Grounds site had little (one fish in July) to no infectivity (three of four exposures with zero prevalence) for either C. shasta or P. minibicornis . In contrast, sentinel salmon exposed at both Bend Bridge and Red Bluff Diversion dam showed similar prevalence of infection per exposure for C. shasta (6–55%) and P. minibicornis (≥ 72%). Spore concentration also showed a downriver trend with Bend and RBDD having the highest concentrations, Anderson River Park and Balls Ferry intermediate, and sites upriver from Bonnyview the lowest (Fig. 3). Higher concentrations occurring in July and August followed by a marked increase in the last sample on 16 November. Both the prevalence of infection and spore concentration data indicates an “infectious zone” between Anderson River Park and RBDD.

We exposed 19 sentinel groups for four days in August (13–17 Aug), September (6–10 Sept), October (5–9 Oct), and November(1–5 Nov) of 2018 at five sites in the Sacramento River. Mortality, during exposure and within five days of return to the wet laboratory, occurred to sentinel groups from RV, SR, and TS in August (33–48%) and September (25–32%). Mean river temperatures at these sites ranged from 17–20⁰ C and columnaris lesions were observed in the affected fish. The August RI cage was lost. C. shasta trophozoites were observed in 32% (91/286) of the intestines while P. minibicornis trophozoites were observed in 17% (48/286) of the kidneys. Like 2016, all infections were rated as CS1 except for three fish in August at RV and RB (CS2). Peak infectivity for both myxozoan parasites was centered near RB and at all sites for the October exposure (Fig. 4). One outlier was the 93% prevalence of C. shasta infection in the RV October group. November had the lowest infection for both parasites at all sites. The RB water samples contained the greatest C. shasta spore concentration (assumed actinospores due to fish infection). As seen in 2016, the reach directly above RB showed the highest C. shasta infectivity. Spore concentration was low at the RI as well as the downriver SR and TS sites (Fig. 5). Fifty percent of all water samples were ≤ 1 C. shasta spore/L, indicating low infectivity to salmon.

Discussion

Both C. shasta and P. minibicornis are common parasites of both juvenile and adult Chinook salmon in the Sacramento River (Hendrickson et al. 1989; Lehman et al. 2020). Adults with the myxospore stage of these parasites are the likely source of the annual polychaete infection (Bartholomew et al. 1997; Foott et al. 2016). In several sample groups (fall-run Chinook juveniles in 2012, 2014, and 2020), the high CS-POI and severity indicate that this myxozoan parasite can reduce out-migrant survival. In contrast, viral and bacterial (potentially excluding F. columnare) pathogens did not demonstrate an overt disease influence on the surveyed juveniles. Given the severity of columnaris disease in sentinel salmon, held in the lower Sacramento at temperatures ≥ 17⁰ C, the effect of F. columnare co-infection in spring out-migrants is an open question (Roon et al. 2015). It is unclear what influence the dual P. minibicornis infection has on Sacramento River salmon health, however the hemorrhagic enteritis induced by C. shasta is likely more significant.

During the study period, the upper Sacramento River above Bend (rkm 415) showed a lower C. shasta infectivity than downstream reaches. The wide range of C. shasta spore concentrations in summer and fall suggests that year-round longitudinal water sampling should be conducted to understand actinospore shedding rates (Hallett et al. 2012; Meaders and Hendrickson 2009). Depending on water temperature, actinospores remain infective for several days post-release facilitating downstream movement and infectivity (Foott et al. 2007). Thus, discrete polychaete populations can influence transmission to salmon a long distance downstream. The moderate CS-POI and severity observed in two of the three sentinel studies and in RBDD natural Winter-run Chinook juveniles do not imply a low health threat to the winter-run population. The influence of limited exposure to localized reaches of high infectivity may help to explain the difference between the diseased 2015 sentinels held upriver of RBDD and wild winter-run juveniles captured at RBDD. Rapid migration through localized zones of high infectivity may reduce the progression of ceratomyxosis by limiting exposure (Ray and Bartholomew 2013).

Several caveats should be considered in evaluating the data of this report: (1) histology has a lower sensitivity than QPCR assay, (2) a minimum of four days between initial infection and invasion of the intestinal tract limits detection in recent infections, (3) challenge “dose” is a function of actinospore concentration and duration of exposure–rapid movement through infectious zones can limit infectivity, and (4) sentinel salmon are exposed to the river for a limited time in comparison to out-migrants yet are presumably stressed by their confinement. The 2014 prognosis groups demonstrated mortality occurs days after the initial capture.

Flow conditions influence salmon infectivity by several mechanisms such as actinospore dilution, migration rate (exposure duration), and polychaete scouring (Alexander et al. 2014; Lehman et al. 2020; Ray and Bartholomew 2013) . No overt relationship between the water year rating and CS-POI was observed in the limited survey data for fall-run (LS) and winter-run (RBDD) Chinook. If a threshold of ≥ 50% CS-POI is used to identify significant disease periods, similar water year types (i.e., Below Normal, Critical, and Dry) are associated with different disease severities. Sample bias (limited number of fish) limits analysis of how water year rating relates to C. shasta infectivity and disease. Better flow indices that could influence polychaete density and associated salmon infection might include maximum flow velocities and duration.

The role of C. shasta in Sacramento River juvenile salmon survival would benefit from a long-term monitoring program. Elements could consist of QPCR analysis of natural juveniles captured at current trap and seine collections, hatchery coded wire tag juveniles captured in the lower river (provide insight into temporal aspect of infectivity), returning adult broodstock intestine for myxospore quantification, sentinel salmon exposures to optimize spatial and temporal aspects, rearing of captured juveniles in non-infectious water to observe the prognosis of infection, and seasonal water sampling to determine spore concentration throughout the Sacramento River. Polychaete survey of likely protected habitats in the Sacramento River (e.g., lee side of hard structures) is another important research question (Stocking and Bartholomew 2007).

Acknowledgements

The findings and conclusions of this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Sample collection assistance from USFWS (RBDD), and CDFW (Tisdale and Knights Landing) with partial funding from the USFWS Wild Fish Survey. Laboratory assay assistance provided by Fish Health Center staff S. Freund, A. Voss, R. Stone, and J. Jacobs. Sentinel salmon supplied by Coleman NFH and river map by T. Spade.

Literature Cited

- Alexander, J. D., S. L. Hallet, R. W. Stocking, L. Xue, and J. L. Bartholomew. 2014. Host and parasite populations after a ten-year flood: Manayunkia speciosa and Ceratonova (syn Ceratomyxa) shasta in the Klamath River. Northwest Science 88(3):219–233.

- Applied Biosystems. 2016. Application Note: Real-time PCR: Understanding Ct. Publication CO019879 0116. Available from: https://www.thermofisher.com/content/dam/LifeTech/Documents/PDFs/PG1503-PJ9169-CO019879-Re-brand-Real-Time-PCR-Understanding-Ct-Value-Americas-FHR.pdf (Accessed September 2018)

- Atkinson, S. D., and J. L. Bartholomew. 2010. Spatial, temporal and host factors structure the Ceratomyxa shasta (Myxozoa) population in the Klamath River basin. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 10:1019–1026.

- Atkinson, S. D., J. S. Foott, and J. L. Bartholomew. 2014. Erection of Ceratonova n. gen. (Myxosporea: Ceratomyxidae) to encompass histozoic species C. gasterostea N. Sp. from threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) and C. shasta n. comb. from salmonid fishes. Journal of Parasitology 100(5):640–645.

- Atkinson, S. D., J. L. Bartholomew, and G. W. Rouse. 2020. The invertebrate host of salmonid fish parasite Ceratonova shasta and Parvicapsula minibicornis (Cnidaria: Myxozoa), is a novel fabriciid annelid, Manayunkia occidentalis sp. nov. (Sabellida: Fabriciidae). Zootaxa 4751(2):310–320.

- Bartholomew, J. L., M. J. Whipple, D. G. Stevens, and J. L. Fryer. 1997. The life cycle of Ceratomyxa shasta, myxosporean parasite of salmonids, requires a fresh-water polychaete as an alternate host. Journal of Parasitology 83:859–868.

- Bartholomew, J. L., S. D. Atkinson, and S. L. Hallett. 2006. Involvement of Manayunkia speciosa (Annelida: Polychaeta: Sabellidae) in the life cycle of Parvicapsula minibicornis, a myxozoan parasite of Pacific salmon. Journal of Parasitology 92:742–748.

- Bjork, S. J., and J. L. Bartholomew. 2009. Effects of Ceratomyxa shasta dose on a susceptible strain of rainbow trout and comparatively resistant Chinook and coho salmon. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 86:29–37.

- Bjork, S. J., and J. L. Bartholomew. 2010. Invasion of Ceratomyxa shasta (Myxozoa) and comparison of migration to the intestine between susceptible and resistant fish host. International Journal of Parasitology 40:1087–1095.

- Foott, J. S., R. Harmon, and R. Stone. 2004. Effect of water temperature on non-specific immune function and ceratomyxosis in juvenile Chinook salmon and steelhead from the Klamath River. California Fish and Game 90:71–90.

- Foott, J. S., R. Stone, E. Wiseman, K. True, and K. Nichols. 2007. Longevity of Ceratomyxa shasta and Parvicapsula minibicornis actinospore infectivity in the Klamath River. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 19:77–83.

- Foott, J. S., R. Stone, R. Fogerty, K. True, A. Bolick, J. L. Bartholomew, S. L. Hallett, G. R. Buckles, and J. D. Alexander. 2016. Production of Ceratonova shasta myxospores from salmon carcasses: Carcass removal is not a viable management option. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 28:75–84.

- Foott, J. S., J. Kindopp, K. Gordon, A. Imrie, and K. Hikey. 2023. Ceratonova shasta infection in lower Feather River Chinook juveniles and trends in water-borne spore stages. California Fish and Wildlife Journal 109:e9.

- Fujiwara, M., M. S. Mohr, A. Greenberg, J. S. Foott, and J. L. Bartholomew. 2011. Effects of Ceratomyxosis on population dynamics on Klamath fall-run Chinook salmon. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 140:1380–1391.

- Hallett, S. L., and J. L. Bartholomew. 2006. Application of a real-time PCR assay to detect and quantify the myxozoan parasite Ceratomyxa shasta in water samples. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 71:109–118.

- Hallett, S. L., R. A. Ray, C. N. Hurst, R. A. Holt, G. R. Buckles, S. D. Atkinson, and J. L. Bartholomew. 2012. Density of the waterborne parasite Ceratomyxa shasta and its biological effects on salmon. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 78:3724–3731.

- Hendrickson, G. L, A. Carleton, and D. Manzer. 1989. Geographic and seasonal distribution of the infective stage of Ceratomyxa shasta (Myxozoa) in northern California. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 7:165–169.

- Humason, G. L. 1979. Animal Tissue Techniques. Fourth edition. WH Freeman and Co., San Francisco, CA, USA.

- Jenkins, J. A., J. D. Bowker, J. R. MacMillan, J. G. Nickum, J. D. Rose, P. W. Sorensen, G. W. Whitledge, J. W. Rachlin, B. E. Warkentine, and H. L Bart. 2014. Guidelines for the Use of Fishes in Research. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, MD, USA.

- Lehman, B. M, R. C. Johnson, M. C. Johnson, O. T. Burgess, R. E. Connon, N. A. Fangue, J. S. Foott, S. L. Hallett, B. Martinez-Lopez, K. M. Miller, M. K. Purcell, N. A. Som, P. V. Donoso, and A. Collins. 2020. Disease in Central Valley salmon: status and lessons from other systems. San Francisco Estuary & Watershed Science 18(3):art2. https://doi.org/10.15447//sfews.2020v18iss3art2

- Meaders, M. D., and G. L. Hendrickson. 2009. Chronological development of Ceratomyxa shasta in the polychaete host, Manayunkia speciosa. Journal of Parasitology 95:1397–1407.

- Poytress, W. R. and F. D. Carillo. 2012. Brood-year 2010 winter Chinook juvenile production indices with comparisons to juvenile production estimates derived from adult escapement. Report of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento, CA, USA.

- Ray, R. A., P. A. Rossignol, and J. L. Bartholomew. 2010. Mortality threshold for juvenile Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in an epidemiological model of Ceratomyxa shasta. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 93:63–70.

- Ray, R. A., and J. L. Bartholomew. 2013. Estimation of transmission dynamics of the Ceratomyxa shasta actinospore to the salmonid host. Parasitology 140(7):907–916.

- Roberts, R. J. 1989. Fish Pathology. Second edition. Bailliere Tindal, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

- Roon, S. R., J. D. Alexander, K. C. Jacobson, and J. L. Bartholomew. 2015. Effect of Nanophyetus salmincola and bacterial co-infection on mortality of juvenile Chinook salmon. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 27:209–216.

- Stocking, R. W., R. A. Holt, J. S. Foott, and J. L. Bartholomew. 2006. Spatial and temporal occurrence of the salmonid parasite Ceratomyxa shasta in the Oregon-California Klamath River Basin. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 18:194–202.

- Stocking, R. W., and J. L. Bartholomew. 2007. Distribution and habitat characteristics of Manayunkia speciosa and infection prevalence with the parasite Ceratomyxa shasta in the Oregon–California Klamath River basin. Journal of Parasitology 93:78–88.

- Sturrock, A. M., W. H. Satterhwaite, K. M. Cervantes-Yoshida, E. R. Huber, H. J. Sturrock, S. Nussle, and S. M. Carlson. 2019. Eight decades of hatchery salmon releases in the California Central Valley: factors influencing straying and resilience fisheries. 44(9):433–444.

- Udey, L. R., J. L. Fryer, and K. S. Pilcher. 1975. Relationship of water temperature to Ceratomyxosis in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri) and coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). Journal of Fisheries Research Board of Canada 32:1545–1551.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and American Fisheries Society-Fish Health Section (AFS-FHS). 2014. Standard procedures for aquatic animal health inspections. Section 2 in Fish Health Section Blue Book: Suggested Procedures for the Detection and Identification of Certain Finfish and Shellfish Pathogens. 2020 edition. Available from: https://units.fisheries.org/fhs/fish-health-sectionblue-book-2020/

- Voss, A., J. S. Foott, and S. Freund. 2020. Myxosporean parasite (Ceratonova shasta and Parvicapsula minibicornis) prevalence of infection in Klamath River basin juvenile Chinook salmon, March–July 2020. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, California–Nevada Fish Health Center, Anderson, CA, USA. http://www.fws.gov/canvfhc/reports.html

- Willson, S. J., M. A. Wilzbach, D. M. Malakauskas, and K. W. Cummings. 2010. Lab rearing of a freshwater polychaete (Manayunkia speciosa, Sabellidae) host for salmon pathogens. Northwest Science 84:182–190.

- Yoshiyama, R. M., E. R. Gerstung, F. W. Fisher, and P. B. Moyle. 2001. Historical and present distribution of chinook salmon in the Central Valley drainage of California. Pages 71–176 in R. L. Brown, editor. Fish Bulletin 179: Contributions to the Biology of Central Valley Salmonids. Volume 1. California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento, CA, USA.