Geographic variation in trace mineral concentrations in blood of mule deer from the Mojave Desert, California, USA

FULL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Vernon C. Bleich* and Kelley M. Stewart

University of Nevada, Reno, Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Science, 1664 North Virginia Street, Mail Stop 186, Reno, NV 89557, USA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5016-1051 (VCB)

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5016-1051 (VCB) https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9643-5890 (KMS)

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9643-5890 (KMS)

*Corresponding Author: vcbleich@gmail.com

Published 28 August 2025 • doi.org/10.51492/cfwj.111.13

Abstract

Minerals are important nutrients and are essential components of the diets of animals. Nutritional requirements or minimum concentrations of minerals for nutritional health are largely unknown for the majority of large, free-ranging herbivores. We investigated concentrations of 9 trace minerals in mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) inhabiting 3 distinct geographic areas—Cima Dome, New York Mountains, and the Mid Hills—in the eastern Mojave Desert, San Bernardino Co., California from 2008 to 2016. These areas differed in vegetative communities, topography, water availability, and fire histories. Telemetered mule deer demonstrated high fidelity to each of these areas, and movement by those individuals between study areas was not detected. During our investigation, overall differences occurred in mean concentrations of magnesium (P < 0.001), calcium (P = 0.022), phosphorus (P = 0.023), potassium (P = 0.042), and selenium (P < 0.001) among the 3 geographic areas. Among years, differences occurred in concentrations of the trace elements investigated in the New York Mountains with the exceptions of magnesium and potassium; at Cima Dome with the exceptions of iron, sodium, potassium, and selenium; and in the Mid Hills with the exceptions of magnesium and zinc. A positive upward trend existed between selenium concentration in the New York Mountains and the year of sample collection (P < 0.05), and a similar—albeit not significant—upward trend was discernible in the Mid Hills, but no such relationship was apparent at Cima Dome. These results emphasize the importance of investigating micronutrient status of mule deer on a local scale and temporally and add to the sparse information available on trace mineral concentrations in mule deer. Despite limited samples (≤165), we make available for the first time reference values for mule deer inhabiting the Mojave Desert, to serve as a baseline against which to measure responses to future environmental perturbations or for comparison with deer occupying other disparate ecosystems, and further contribute to the derivation of reference values for mule deer in general.

Key words: California, geographic variation, macronutrients, micronutrients, Mojave Desert, mule deer, nutrition, Odocoileus hemionus, temporal variation, trace minerals

| Citation: Bleich, V. C., and K. M. Stewart. 2025. Geographic variation in trace mineral concentrations in blood of mule deer from the Mojave Desert, California, USA. California Fish and Wildlife Journal 111:e13. |

| Editor: Arjun Dheer, Wildlife Branch |

| Submitted: 1 October 2024; Accepted: 8 May 2025 |

| Copyright: ©2025, Bleich and Stewart. This is an open access article and is considered public domain. Users have the right to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles in this journal, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, provided the authors and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife are acknowledged. |

| Competing Interests: The authors have not declared any competing interests. |

Introduction

Minerals are important nutrients in the body, but represent a small fraction of total composition, usually < 5% (Robbins 1993; Barboza et al. 2009). Mineral requirements or levels of toxicity for animals may vary with age, sex, species, season, growth stage, and reproductive state of individuals (Kalinsinska 2019), but actual requirements for most species of wildlife have not yet been determined (Robbins 1993; Barboza et al. 2009). Although other nutrients including sources of protein and energy are of primary interest with respect to body condition, deficiencies of minerals are important and can affect fertility, productivity, and survival (Robbins 1993). Minerals also play important roles in disease resistance, antler growth or strength, recruitment, and vital rates of large herbivorous mammals (French et al. 1956; Bowyer 1983; Flueck 1991; Failla 2003; O’Hara et al. 2001; Johnson et al. 2007). As a result, mineral concentrations often vary among tissues or organs responsible for the multitude of physiological processes in the bodies of animals (Barboza et al. 2009).

Despite their importance to animal health, some minerals can be toxic or otherwise harmful if they are overabundant in the diet or in animal tissues (McDowell 2003; Pond et al. 2005; Radostits et al. 2007; Duffy et al. 2009; Hernandez et al. 2017; Herrada et al. 2024; Bedouet et al. 2025). Indeed, at the population level, mineral deficiencies or toxicities may both be overlooked and attributed to other factors such as food shortage, parasites, infectious agents, or even severe weather (Robbins 1993). In the absence of information pertaining to mineral concentrations in wildlife, it is impossible for managers to ascertain if those levels are adequate, deficient, or toxic (Kalisinska 2019). As a result, the potential for micronutrient levels to affect individual animals or entire populations remains speculative.

In a classic example illustrating the importance of trace minerals, antlers of tule elk (Cervus canadensis nannodes) occupying the Owens Valley in Inyo County, California develop normally in size and conformation but long have been known to break easily during the mating season when males compete for breeding opportunities (McCullough 1969). Although overall forage quality is an important contributor to antler quality, bone fragility has been associated with mineral imbalances (French et al. 1956; Underwood 1977; Gogan et al. 1988; Bleich 1990; Robbins 1993). This observation is particularly true in tule elk, which generate great interest among hunters and non-hunters alike, and are valued highly for aesthetic, recreational, and economic reasons. A very high proportion of males inhabiting the Owens Valley exhibited broken antler tines (82%), and 36% had broken main beams shortly after the onset of rut (Johnson et al. 2005). McCullough (1969) attributed the high proportion of males exhibiting broken antlers to a probable mineral imbalance involving inadequate amounts of calcium, but not phosphorus, which was confirmed many decades later by Johnson et al. (2007).

Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) are popular big game animals and also generate tremendous interest among the general public. Mule deer are widely distributed across western North America (Heffelfinger and Latch 2023; Jensen et al. 2023), but little is known is known about mineral nutrition despite the widespread distribution of that species. Although numerous authors have investigated trace element concentrations in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), similar contributions to the literature on mule deer since that of Anderson (1981) are few. The information presented herein augments the few data currently available (Anderson 1981; Anderson and Medin 1982; DelGiudice et al. 1990; Zimmerman et al. 2008; Myers et al. 2015; Roug et al. 2015) for mule deer, and most of which were subject to the limitations associated with small sample sizes (Friedrichs et al. 2012; Appendix I). As a result, information presented herein is of particular value (Myers et al. 2015).

In this paper, we describe concentrations of 9 trace elements (the micro-minerals iron, copper, zinc, and selenium, and macro-minerals calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, and sodium) in the blood of mule deer occupying three distinct geographic regions of the Mojave Desert wherein those cervids occupy a variety of habitats. Fidelity to these habitat types in which deer were captured and the lack of movement among the three regions of the study area, strong selection for the habitat types represented by each region, and differing landforms and vegetation among the three regions (Bush 2015; McKee et al. 2015; Heffelfinger et al. 2018) provided the opportunity to (1) evaluate trace mineral concentrations in the blood of adult female mule deer on a local basis; (2) test for differences in blood parameters among animals sampled from populations occupying 3 Mojave Desert vegetation types; and (3) provide reference values for mule deer occupying the Mojave Desert using data that are not conflated with results from other disparate systems.

Methods

Study Area

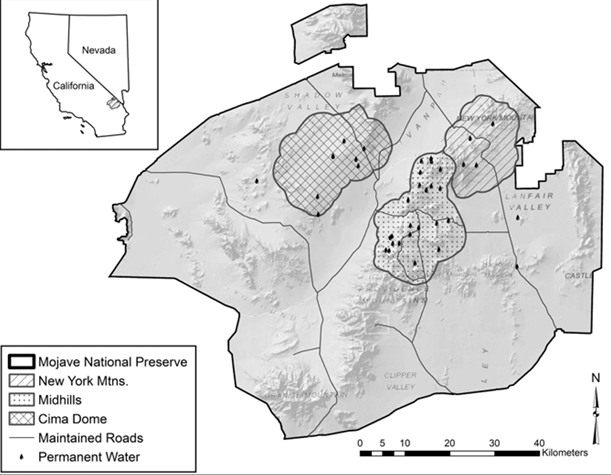

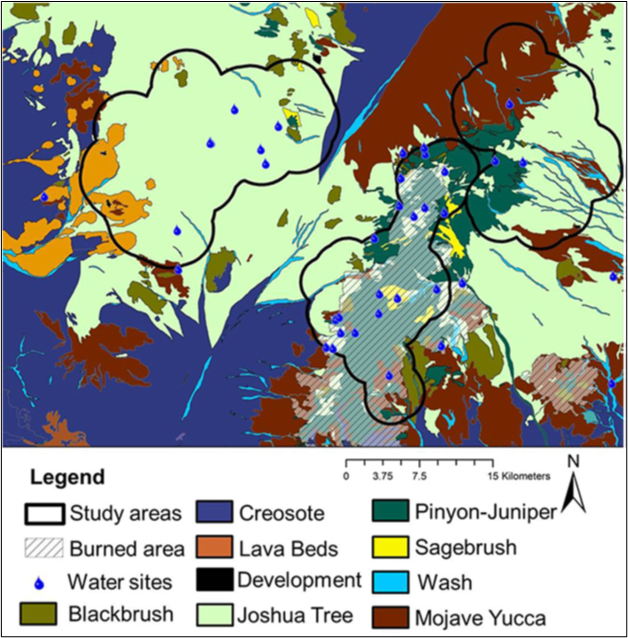

Our study area was located in the eastern Mojave Desert, San Bernardino County, California, and was bounded on the north and south by U.S. Interstate Highways 15 and 40, respectively, on the west by Kelbaker Rd., and on the east by the California-Nevada state line, wherein we investigated mule deer ecology from 2008 to 2016 (Bush 2015; McKee et al. 2015; Heffelfinger et al. 2018, 2020). Vegetation assemblages representative of the Great Basin, Mojave, and Sonoran deserts create heterogeneity across the landscape (Thomas et al. 2004), which is characterized by distinct, rugged, mountain ranges separated by bajadas, playas, or dunes, and elevations range from 270 m to 2,400 m (Thorne et al. 1981; McKee et al. 2015). The study area lies within a legislatively defined area administered by the National Park Service (NPS) known as the Mojave National Preserve (Fig. 1; Pauli and Bleich 1999). Climate is xeric and representative of the Mojave Desert in general, and is characterized by high summer temperatures and limited annual precipitation that is bimodal with peaks during winter and summer seasons (Hereford et al. 2004), although inter-annual and spatial variation in precipitation both are substantial (Rundel and Gibson 1996). Elevation and landform play important roles in determining precipitation and temperature on a local basis in the eastern Mojave Desert (Bleich 2017), contributing further to heterogeneity of vegetation and affecting forage quality, forage availability, or both (Bleich et al. 1992, 1997). Moreover, concentrations of trace elements in forage species have been shown to vary across the region (Bleich et al. 2017).

We identified 3 distinct geographic regions of the eastern Mojave Desert as the New York Mountains (35°17′ N, 115°15′ W), Cima Dome (35°18′ N, 115°35′ W), and the Mid Hills (35°07′ N, 115°25’W). Each of these areas was inhabited by mule deer (Bleich and Pauli 1999; Bush 2015; McKee et al. 2015; Heffelfinger et al. 2018) and characterized by distinctive topography, habitat type, and availability of water (Figs. 1 and 2). Vegetation in the New York Mountains was dominated by pinyon-juniper (Pinus spp. – Juniperus osteosperma) woodland at upper elevations and desert scrub at lower elevations (McKee et al. 2015; Heffelfinger et al. 2018). Vegetation at Cima Dome was dominated by Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia) woodland, and vegetation in the Mid Hills was pinyon pine-juniper woodland that experienced a massive (285 km2) conflagration 3 years prior to the onset of our investigation (Casebier 2005). As a result of that fire, vegetation within the burn was dominated by globemallow (Sphaeralcea spp.), bitterbrush (Purshia sp.), and desert almond (Prunus fasciculata) during our research. Surface water available to mule deer occurred at a mean density of 0.01 sources/km2 in the New York Mountains, 0.02 sources/km2 at Cima Dome, and 0.08 sources/km2 in the Mid Hills (McKee et al. 2015).

Sample Collection

We used a helicopter and net-gun to capture mule deer (Krausman et al. 1985). Most animals were transported to a central processing area where morphometrics were determined, and biological samples were collected. From 2013 to 2016, we also measured nutritional condition of adult females (Monteith et al. 2013) using standard protocols developed and validated for mule deer (Stephenson et al. 2002; Cook et al. 2007, 2010), and we used ultrasonography to ascertain pregnancy (Stephenson et al. 1995). Several individuals processed in the field because of the distance from the location of capture to the processing area were not examined for pregnancy or body condition. Regardless of processing location, all animals were fitted with a Global Positioning System (GPS) telemetry collar (Wildlife GPS Datalogger, Sirtrack, Havelock North, New Zealand; McKee et al. 2015). Animals processed at a central area were transported back to the capture location prior to being released, and all animals processed in the field were released at the site of capture.

We collected blood by jugular venipuncture using a 25-mm, 18-gauge needle and a 60-ml syringe. We placed whole blood from each deer in a trace element EDTA collection tube for selenium analysis; an additional sample was placed in an additive-free trace element collection tube to be analyzed for calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, and zinc. Those samples were centrifuged for ~12 minutes at ~1,750×g the day of collection, after which we transferred the serum to a new trace element collection tube. Samples then were placed on ice and kept refrigerated until delivered to the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory at the University of California, Davis where samples were prepared and analyzed for the elements of interest using inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (Poppenga et al. 2012). Reporting limits were 2.0 and 0.1 mEq/l for sodium and potassium, respectively; 2 ppm for calcium; 1 ppm for phosphorus and magnesium; 0.2 ppm for iron; 0.05 ppm for zinc and copper; and 0.010 ppm for selenium.

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Nevada, Reno (IACUC Protocol #00538). Additionally, methods were in keeping with guidelines established by the American Society of Mammalogists for research on wild mammals (Gannon et al. 2007; Sikes et al. 2011, 2016), and followed capture and handling procedures developed by the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG 2007).

Statistical Analyses

We collected samples during late winter (i.e., late February or early March) from deer occupying three distinct areas and over a period of up to nine years, and composited analytical results from the three geographic areas across years to obtain an overall estimate for each trace mineral representative of the entire study area (i.e., the eastern Mojave Desert). We explored the potential for differences in trace element concentrations among areas, and also among years of sample collection within each of the 3 areas. We used one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to test for an overall difference (α = 0.05) among mean values of analytes for deer occupying the New York Mountains, Cima Dome, or the Mid Hills. Similarly, we used one-way ANOVA to test for differences among mean values of analytes among years within each of those geographic areas. If mean values of analytes differed among areas, we relied on Tukey’s HSD to make pairwise comparisons (Zar 2010). In addition, we used Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient to examine relationships between concentrations of selenium—the only element with a sufficiently long data stream (9 years)—and year of collection for the New York Mountains and Cima Dome—neither of which had experienced large wildfires for at least several decades—as well as the Mid Hills, which had experienced a massive wildfire three years prior to the onset of our investigation.

We composited analytical results from the three geographic areas across years and used Reference Value Advisor (Greffre et al. 2011)—an Excel Spreadsheet add-in—to evaluate each variable for distribution and outliers, to calculate descriptive statistics, and to establish reference values for mule deer occupying the eastern Mojave Desert. Reference Value Advisor used Tukey’s Test to flag outliers and confirmed them with the Dixon-Reed Test (Greffre et al. 2011). These are the first data on trace mineral concentrations from mule deer occupying the Mojave Desert and, with one exception, we had no compelling reason to exclude suspect data (Greffre et al. 2009). With respect to potassium, we excluded results for 11 samples (x̅ = 19.45 mEq/L, range 12–44) collected consecutively on a single day from two of the geographic areas, and that likely represented pseudohyperkalemia when compared to results for all other samples collected during our investigation (x̅ = 5.16 mEq/L, range 3.8–7.9). Pseudohyperkalemia is an elevation of potassium in blood serum and frequently results from improper collection, handling, or storage of a sample, but does not represent the level of potassium in vivo (De Rosales et al. 2017).

Results

We obtained blood from 194 mule deer captured in the New York Mountains (n = 66), at Cima Dome (n = 59), or in the Mid Hills (n = 69) during winter from 2008 to 2016. Differences occurred in mean concentrations of magnesium (F2,92 = 10.07, P < 0.001), calcium (F2,92 = 3.95, P = 0.022), phosphorus (F2,91 = 3.92, P = 0.023), potassium (F2,81 = 3.29, P = 0.042), and selenium (F2,162 = 25.85, P < 0.001) among the New York Mountains, Cima Dome, and the Mid Hills (Table 1). Among years, differences occurred in concentrations of all trace elements in the New York Mountains with the exceptions of magnesium and potassium (Table 2); at Cima Dome with the exceptions of iron, potassium, and selenium (Table 3); and in the Mid Hills with the exceptions of magnesium and zinc (Table 4). In the New York Mountains a positive upward trend existed between selenium concentration and the year of collection (n = 6, rs = 0.893, P < 0.05), and a similar—albeit not significant—upward trend was discernible in the Mid Hills (n = 6, rs = 0.309); no such relationship was apparent at Cima Dome (n = 6, rs = 0.058). Reference values for analytes from all three areas and all years combined are presented in Table 5.

Table 1. ANOVA results comparing concentrations of 9 analytes for female mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus ssp.) occupying three distinct regions of the eastern Mojave Desert, mean (± SE) of all sampling years combined, in Mojave National Preserve, San Bernardino County, California, 2008–2016. Where ANOVA identified significant differences among the 3 areas, Tukeys HSD revealed pairwise differences in mean concentrations of magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, and selenium, which are indicated by differing superscripts (‘a’ and ‘b’). Mean values for potassium exclude samples from 11 deer in which potassium concentrations were substantially elevated and likely represented pseudohyperkalemia (De Rosales et al. 2017), as explained in the text.

| Analyte (units) | ANOVA Results | New York Mtns | Cima Dome | Mid Hills |

| Fe (ppm) | F2,92 = 2.01, P = 0.140 | 1.81 ± 0.124 | 1.53 ± 0.081 | 1.70 ± 0.074 |

| Mg (ppm) | F2,92 = 10.07, P < 0.001 | 36.31a ± 0.690 | 32.52b ± 0.963 | 31.97b ± 0.610 |

| Zn (ppm) | F2,92 = 2.16, P = 0.121 | 1.17 ± 0.121 | 0.86 ± 0.063 | 1.05 ± 0.106 |

| Cu (ppm) | F2,92 = 2.59, P = 0.080 | 1.07 ± 0.088 | 0.94 ± 0.078 | 0.84 ± 0.050 |

| Ca (ppm) | F2,92 = 3.95, P = 0.022 | 95.0a ± 2.334 | 85.45b ± 2.664 | 85.50b ± 3.180 |

| P (ppm) | F2,91 = 3.92, P = 0.023 | 62.28a ± 2.620 | 48.55b ± 3.750 | 59.91 ± 4.227 |

| Na (mEq/L) | F2,92 = 1.34, P = 0.267 | 158.13 ± 2.436 | 153.79 ± 1.884 | 154.71 ± 1.477 |

| K (mEq/L) | F2,81 = 3.29, P = 0.042 | 5.45 ± 0.197 | 4.92 ± 0.148 | 4.89 ± 0.160 |

| Se (ppm) | F2,162 = 25.85, P < 0.001 | 0.215a ± 0.0102 | 0.137b ±0.0080 | 0.208a ± 0.0066 |

Table 2. Means (±SE) from analysis of variance (ANOVA test statistic and p-value) for 9 trace minerals in female mule deer compared among years in the New York Mountains in Mojave National Preserve, San Bernardino County, California, 2008–2016. (Note: no data for 2010 and 2013)

| Analyte (units) | ANOVA | P | 2008 | 2009 | 2011 | 2012 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Iron (ppm) | F3,28 = 3.39 | 0.032 | 1.29 ± 0.131 | 2.35 ± 0.286 | 1.63 ± 0.181 | 1.86 ± 0.222 | — | — | — |

| Magnesium (ppm) | F3,28 = 1.01 | 0.403 | 33.60 ± 1.208 | 37.25 ± 1.532 | 36.50 ± 1.164 | 36.31 ± 0.690 | — | — | — |

| Zinc (ppm) | F3,28 = 9.34 | <0.001 | 0.54 ± 0.084 | 1.85 ± 0.286 | 1.24 ± 0.135 | 0.71 ± 0.053 | — | — | — |

| Copper (ppm) | F3,28 = 6.97 | 0.002 | 0.66 ± 0.045 | 1.23 ± 0.171 | 1.38 ± 0.140 | 0.67 ± 0.059 | — | — | — |

| Calcium (ppm) | F3,28 = 7.44 | <0.001 | 95.20 ± 0.482 | 93.25 ± 1.645 | 87.17 ± 3.688 | 110.28 ± 4.063 | — | — | — |

| Phosphorus (ppm) | F3,28 = 4.86 | <0.008 | 73.20 ± 6.514 | 59.75 ± 2.590 | 53.42 ± 4.389 | 72.57 ± 4.116 | — | — | — |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | F3,28 = 5.51 | 0.004 | 150.00 ± 3.162 | 147.50 ± 5.261 | 166.67 ± 3.760 | 161.43 ± 1.429 | — | — | — |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | F2,21 = 1.7 | 0.207 | 5.16 ± 0.244 | — | 5.26 ± 0.246 | 6.00 ± 0.468 | — | — | — |

| Selenium (ppm) | F5,52 = 3.04 | 0.018 | 0.16 ± 0.017 | — | 0.17 ± 0.010 | 0.22 ± 0.064 | 0.23 ± 0.019 | 0.22 ± 0.032 | 0.27 ± 0.021 |

Table 3. Means (±SE) from analysis of variance (ANOVA statistic and p-value) for 9 trace minerals in blood of female mule deer compared among years at Cima Dome in Mojave National Preserve, San Bernardino County, California, 2008–2016. (Note: no data for 2010 and 2013)

| Analyte (units) | ANOVA | P | 2008 | 2009 | 2011 | 2012 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Iron (ppm) | F3,25 = 0.95 | 0.432 | 1.50 ± 0.167 | 1.41 ± 0.114 | 1.73 ± 0.191 | 1.45 ± 0.132 | — | — | — |

| Magnesium (ppm) | F3,25 = 7.18 | 0.002 | 28.83 ± 0.910 | 29.80 ± 0.940 | 36.78 ± 1.862 | 35.25 ± 2.056 | — | — | — |

| Zinc (ppm) | F3,25 = 8.50 | < 0.001 | 0.51 ± 0.034 | 0.87 ± 0.112 | 1.16 ± 0.070 | 0.73 ± 0.083 | — | — | — |

| Copper (ppm) | F3,25 = 19.45 | < 0.001 | 0.73 ± 0.045 | 0.75 ± 0.057 | 1.46 ± 0.125 | 0.60 ± 0.040 | — | — | — |

| Calcium (ppm) | F3,25 = 8.29 | < 0.001 | 89.00 ± 1.366 | 82.60 ± 3.015 | 76.44 ± 5.135 | 107.50 ± 2.500 | — | — | — |

| Phosphorus (ppm) | F3,25 = 8.25 | < 0.001 | 45.00 ± 5.780 | 40.60 ± 3.509 | 44.33 ± 6.784 | 83.25 ± 5.121 | — | — | — |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | F3,25 = 12.68 | < 0.001 | 146.67 ± 2.108 | 147.00 ± 2.134 | 163.33 ± 2.887 | 160.00 ± 0.000 | — | — | — |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | F3,25 = 1.88 | 0.159 | 4.55 ± 0.184 | 4.70 ± 0.148 | 5.16 ± 0.393 | 5.53 ± 0.184 | — | — | — |

| Selenium (ppm) | F5,43 = 1.00 | 0.431 | 0.18 ± 0.055 | — | 0.11 ± 0.015 | 0.13 ± 0.018 | 0.12 ± 0.016 | 0.15 ± 0.012 | 0.15 ± 0.015 |

Table 4. Means (±SE) from analysis of variance (ANOVA statistic and p-value) for 9 trace minerals in female mule deer compared among years in the Mid Hills in Mojave National Preserve, San Bernardino County, California, 2008–2016. (Note: no data for 2010 and 2013)

| Analyte (units) | ANOVA | P | 2008 | 2009 | 2011 | 2012 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron (ppm) | F3,30 = 8.38 | < 0.001 | 1.64 ± 0.173 | 1.34 ± 0.076 | 1.94 ± 0.101 | 2.08 ± 0.120 | — | — | — |

| Magnesium (ppm) | F3,30 = 1.60 | 0.21 | 31.29 ± 1.782 | 30.45 ± 0.790 | 33.36 ± 1.170 | 33.20 ± 0.583 | — | — | — |

| Zinc (ppm) | F3,30 = 2.8 | 0.057 | 0.54 ± 0.033 | 1.23 ± 0.146 | 1.26 ± 0.242 | 0.94 ± 0.218 | — | — | — |

| Copper (ppm) | F3,30 = 33.46 | < 0.001 | 0.63 ± 0.037 | 0.72 ± 0.040 | 1.20 ± 0.060 | 0.62 ± 0.016 | — | — | — |

| Calcium (ppm) | F3,30 = 30.01 | < 0.001 | 90.00 ± 2.093 | 87.091 ± 2.226 | 67.18 ± 4.251 | 116.00 ± 2.450 | — | — | — |

| Phosphorus (ppm) | F3,29 = 5.97 | < 0.003 | 55.86 ± 8.362 | 57.27 ± 6.093 | 48.5 ± 7.032 | 94.20 ± 4.862 | — | — | — |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | F3,30 = 6.49 | < 0.002 | 150.00 ± 0 | 150.00 ± 1.907 | 158.18 ± 2.960 | 164.00 ± 2.450 | — | — | — |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | F3,27 = 4.63 | 0.01 | 5.61 ± 0.466 | 4.39 ± 0.136 | 4.57 ± 0.178 | 5.40 ± 0.324 | — | — | — |

| Selenium (ppm) | F5,52 = 3.92 | < 0.005 | 0.12 ± 0.016 | — | 0.21 ± 0.018 | 0.20 ± 0.035 | 0.21 ± 0.017 | 0.21 ± 0.009 | 0.20 ± 0.008 |

Table 5. Descriptive statistics, reference intervals, and 90% confidence intervals for lower and upper confidence limits determined for female mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in Mojave National Preserve, San Bernardino County, California, 2008–2016.

| Analyte (units) | n | Mean | SD | Median | Range | Reference Interval | 90% CI Lower | 90% CI Upper |

| Iron (ppm) | 95 | 1.68 | 0.544 | 1.60 | 0.6–3.7 | 0.714–3.160 | 0.600–0.960 | 2.662–3.700 |

| Magnesium (ppm) | 95 | 33.6 | 4.60 | 33.0 | 23–47 | 25.8–46.0 | 23.0–27.0 | 41.0–47.0 |

| Zinc (ppm) | 95 | 1.03 | 0.581 | 0.880 | 0.38 –3.50 | 0.410–3.000 | 0.380–0.460 | 2.100–4.500 |

| Copper (ppm) | 95 | 0.95 | 0.417 | 0.81 | 0.46–2.70 | 0.500–2.760 | 0.467–0.503 | 1.756–2.337 |

| Calcium (ppm) | 95 | 88.7 | 16.10 | 89.0 | 32–120 | 59.4–120.0 | 32.0–62.6 | 116.0–120.0 |

| Phosphorus (ppm) | 94 | 56.36 | 21.260 | 54.50 | 8.9–100.0 | 20.13–100.0 | 8.90–26.0 | 97.25–100.0 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 95 | 155.6 | 11.10 | 160.0 | 120–200 | 140.0–180.0 | 120.0–140.0 | 170.0–200.0 |

| Potassium (mEq/L)a | 84 | 5.06 | 0.910 | 4.85 | 3.7–7.9 | 3.71–7.65 | 3.70–4.10 | 6.80–7.90 |

| Selenium (ppm) | 165 | 0.186 | 0.7250 | 0.180 | 0.05–0.50 | 0.078–0.368 | 0.050–0.091 | 0.300–0.500 |

Discussion

Although mule deer have been studied extensively across their range, trace mineral concentrations rarely have been reported, thereby enhancing the utility of our results (Myers et al. 2015). Indeed, few authors have provided such information (Appendix I), and reference intervals of trace elements in blood (Table 5) previously have not been reported for mule deer (Myers et al. 2015) or for the majority of wild species. Ours is the first effort to generate reference values for trace minerals in the blood of mule deer and were derived at a localized scale. Thus, readers should interpret our results in the context of those available for other North American cervids or domestic livestock, and acknowledge the limitations associated with that approach (Myers et al. 2015).

Data presented herein provided the opportunity to compare values for mule deer occupying three distinct habitat types within the Mojave Desert (Table 1). Mean values of iron, zinc, copper, and sodium did not differ among the three areas and were similar to those for other populations of mule deer for which limited information is available (Oliver et al. 2000; Appendix I), as well as for white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus ssp.) and domestic livestock (Kie et al. 1983; Puls 1994; Chitwood et al. 2013). Mean values for magnesium, calcium, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium differed among the three areas but, with the exception of phosphorus, generally were within the ranges of values available in the literature (Appendix I). Mean levels of phosphorus were low relative to ranges previously reported for mule deer (Appendix I), which was unanticipated given the recent fire in the Mid Hills and the role of fire in recycling that essential nutrient (Butler et al. 2018).

Despite differences in mean concentration of potassium in blood of mule deer occupying the Mid Hills (x̅ = 5.61 mEq/l) and those occurring at Cima Dome (x̅ = 4.55 mEq/l), both values were within the ranges of values reported for mule deer elsewhere (Appendix I). A difference also existed in the concentrations of magnesium in mule deer occupying the New York Mountains (x̅ = 33.6 ppm) and those occupying Cima Dome (28.83 ppm), but those values also were within the ranges of magnesium reported previously for that taxon (Appendix I). The low values at Cima Dome may have reflected differences in substrate chemistry when compared to the Mid Hills or the New York Mountains. Additionally, the recent fire in the Mid Hills may have resulted in a temporary increase in concentrations of potassium in vegetation (Ohr and Bragg 1985). Moreover, biomass of preferred forage may have increased after the fire; although total mineral mass is generally not affected by fire, availability of some minerals on xeric sites is temporarily increased because of release from litter or from standing perennial plant material (Merrill et al. 1980). Finally, we cannot rule out the potential for a sample size effect, which may become less apparent with additional sampling.

Similar to results reported by earlier investigators (Anderson and Medin 1982; Myers et al. 2015; Roug et al. 2015), we found annual differences among the populations sampled, among locations (Table 1) or among years, but on a much smaller geographic scale (Tables 2–4). Seasonal variation in mineral concentrations is known to occur (Borch-Iohnsen and Nilssen 1987; Staaland and Hove 2000), and our samples were obtained during the same period each year. That alone, however, may not rule out within-year seasonal effects of localized precipitation on plant productivity and resultant declines or increases in forage availability. It is possible that our findings reflect individual variation within each of the three populations we investigated rather than covarying with annual precipitation or other climatological factors. Nevertheless, herbivores derive minerals from the forage consumed and the concentrations of minerals in vegetation—or combined with osteophagy (Krausman and Bissonette 1977; Bowyer 1983; Warrick and Krausman 1986; Keating 1989) or geophagy (Holl and Bleich 1987; Ayotte et al. 2006) potentially to supplement uptake of minerals—and that ultimately is a function of edaphic factors dependent on the underlying geology of the area in question (Van Soest 1994). The geological substrate did not change in any of the areas we investigated.

Differences between fire histories in the New York Mountains, at Cima Dome—neither of which had burned in recent decades—and the Mid Hills could provide insight into differences in selenium concentrations among deer occupying each of those areas, but wildfire has been shown to play only a minor role in selenium availability (Burton et al. 2016). Although plant succession was ongoing in the Mid Hills throughout our investigation and there was a general upward trend in selenium concentrations in mule deer over 9 years, this relationship likely is not readily explained by fire history. Further, a stronger and significant upward trend in selenium concentration occurred among deer inhabiting the New York Mountains (rs = 0.893), an area that was not impacted by wildfire, and there was virtually no relationship between selenium concentration and time at Cima Dome (rs = 0.058), neither of which had experienced recent conflagrations. Thus, multiple local factors likely influence results and, as emphasized previously (Pierce and Bleich 2003, Bleich et al. 2019), demonstrates the value of sampling at scales that reflect differing ecological or temporal settings (Appendix I).

Despite increasing interest in nutrition and its importance to population performance (Monteith et al. 2023), information on geographic or temporal variation in mineral content of various forage species remains poorly researched (Bleich et al. 2017). Variability in habitat selection by mule deer in the eastern Mojave Desert provided the opportunity to explore that question and add to the scant information available on trace elements in the blood of this widely distributed cervid. Environmental change—whether the result of stochastic events such as fire or extreme weather, long-term responses of vegetation to increased atmospheric CO2 (Hamerlynck et al. 2000), climate change (Hantson et al. 2021), seasonal variation in rainfall (Greene et al. 1987, Sprinkle et al. 2000), seasonal changes in plant phenology (Staaland and Hove 2000), or the result of pollution from a variety of sources—singly or collectively has the potential to alter soil chemistry and resulting levels of micro-minerals or macro-minerals in soils, forage, or in wildlife itself (Harrison and Dyer 1984; Flueck 1991; Basanta et al. 2002; Garcia-Marco and Gonzalez-Prieto 2008; Duffy et al. 2009). Moreover, the large wildfire in the Mid Hills (Casebier 2005) just prior to the onset of our investigation, and additional wildfires at Cima Dome (McAuliffe 2021) and in the New York Mountains (Thornton 2023) shortly after our investigation ended, recently have altered the composition of vegetation across extensive portions of our study areas. These events provide heretofore unprecedented opportunities for continuing investigations of vegetation succession, its effect on the chemical composition of mule deer forage, and trace element concentrations among mule deer occupying a variety of habitat types across a xeric desert ecosystem; as yet, those opportunities have not been realized.

Nutritional requirements are not well understood for most species of wildlife (Robbins 1993; Johnson et al. 2007; Barboza et al. 2009), but mule deer are among the most widely distributed ungulates native to North America (MDWG 2004; Heffelfinger and Latch 2023; Jensen et al. 2023). Rather than assuming that information or descriptive statistics from a single location are representative across the range of this taxon, differences among geographic areas or populations should be anticipated (Pierce and Bleich 2003). It would be useful if a range of values or thresholds for deficiency (or toxicity) of mineral concentrations for mule deer were established (Myers et al. 2015) for use as baselines against which to compare changes resulting from environmental perturbations (Duffy et al. 2009), or as precursors to a lowered immune response and its potential for population-level effects of disease (Downs and Stewart 2014). Additionally, a better understanding of mineral availability and metabolism, and their roles in population ecology of large herbivores would be of value (Flynn et al. 1977; Robbins et al. 1985; Frank et al. 1994; O’Hara et al. 2001; Barboza et al. 2003). Such information also will help in determining the relevance of these elements in the overall health of local populations (Myers et al. 2015), and population biology—especially in the form of life-history investigations—is among the most promising areas of micronutrient ecology, in that variation in clutch size and body size of offspring may be a function of ecosystem biogeochemistry (Kaspari 2021). Indeed, long-term screening will advance understanding of population-level and individual-animal concentrations of trace elements in the context of population health (Poppenga et al. 2012), geographic location (Bleich et al. 2017), or environmental conditions (Pierce and Bleich 2003).

Many environmental factors affect mineral concentrations in forage consumed by large herbivores (Staaland and Hove 2000; Staaland and White 2001; Poppenga et al. 2012; Bleich et al. 2017). Among these are landscape features (Kozakiewicz et al. 2018), differences in elemental concentrations in substrate (Carlisle and Cleveland 1958; Hunt 1966; Lisk 1972; Van Soest 1994; Banuelos and Ajwa 1999), seasonal variation in rainfall (Greene et al. 1987; Sprinkle et al. 2000), moisture content of forage (Holl and Bleich 1987), diet at the time of sample collection (Johnson et al. 2007; Rosen et al. 2009; Bleich et al. 2017; Myers et al. 2015), and demographic characteristics (Pollock 2005). Further, handling and processing of samples (Ellervik and Vaught 2015), capture techniques (Kock et al. 1987), or other environmental stressors (Gartner et al. 1965; Duffy et al. 2009) also may influence analytical results.

Results reported herein add to the paucity of existing information on trace element concentrations in mule deer and emphasize the value of detailed sampling under a variety of ecological conditions, both spatially and temporally (Kie et al. 1983; Chitwood et al. 2013), and the importance of long-term monitoring of populations (Monteith et al. 2023). Deficiencies in trace minerals may be widespread, but the incidence of such underestimated because subclinical forms of deficiency can occur and go unnoticed or be attributed to other factors (Robbins 1993; Barboza et al. 2003; Radostits et al. 2007:1698–1699). Additionally, our findings emphasize the value of detailed sampling at multiple locations within the distribution of any particular species (Pierce et al. 2003; Bleich et al. 2019) and is information that may be useful when evaluating future conservation objectives (Reeves et al. 2024). Consistent with the recommendation of Anderson and Medin (1982), we encourage investigators to continue to add to our understanding of mineral content of forage, its effect on large, native herbivores—mule deer in particular—and to further explore variation in trace element concentrations among populations of this widely distributed species.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Gonzales, A. Adams, and B. Munk (CDFW) for providing sampling expertise, veterinary guidance, and watchful eyes during the capture and collaring process. We thank R. Poppenga, L. Konde, and N. Shirkey for providing analytical results and copies of original data sheets. S. deJesus of Landells Aviation; T. Evans, T. Glenner, C. Schroeder, K. Monteith, S. Morano, and J. Villepique (CDFW); and the pilots and capture specialists of Quicksilver Air and Leading Edge Aviation provided safe and efficient aerial support. D. Schramm, L. Whalon, and N. Darby (NPS) provided enduring support for our mule deer research at Mojave National Preserve. We thank numerous other CDFW, NPS, and volunteer personnel for assisting with animal handling or record keeping. This is Professional Paper 154 from the Eastern Sierra Center for Applied Population Ecology.

Literature Cited

- Anderson, A. E. 1981. Morphological and physiological characteristics. Pages 27–97 in O. C. Wallmo, editor. Mule and Black-tailed Deer of North America. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE, USA.

- Anderson, A. E., and D. E. Medin. 1982. Blood serum electrolytes in a Colorado mule deer population. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 8:183–190.

- Ayotte, J. B., K. L. Parker, J. M. Arocena, and M. P. Gillingham. 2006. Chemical composition of lick soils: functions of soil ingestion by four ungulate species. Journal of Mammalogy 87:878–888.

- Banuelos G. S., and H. A. Ajwa. 1999. Trace elements in soils and plants: an overview. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 34:951–974.

- Barboza, P. S., K. L. Parker, and I. D. Hume. 2009. Integrative Wildlife Nutrition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- Barboza, P. S., E. P. Rombach, J. E. Blake, and J. A. Nagy. 2003. Copper status of muskoxen: a comparison of wild and captive populations. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 39:610–619.

- Basanta, M. R., M. Diaz-Ravina, S. J. Gonzalez-Prieto, and T. Carballas. 2002. Biochemical properties of forest soils as affected by a fire retardant. Biology and Fertility of Soils 36:377–83.

- Bedouet, L., M.-P. Ryser-Degiorgis, S. Borel, C. Amiot. E. Afonso, and M. Coeurdassier, 2025. Evaluating trace elements as a conservation concern for Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in Switzerland. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 298:118300.

- Bleich, V. C. 1990. On calcium deficiency and brittle antlers. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 26:588.

- Bleich, V. C. 2017. Leucism in bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), with special reference to the eastern Mojave Desert, California and Nevada, USA. Desert Bighorn Council Transactions 54:31–47.

- Bleich, V. C., and A. M. Pauli. 1999. Distribution and intensity of hunting and trapping activity in the East Mojave National Scenic Area, California. California Fish and Game 85:148–160.

- Bleich, V. C., R. T. Bowyer, D. J. Clark, and T. O. Clark. 1992. Quality of forages eaten by mountain sheep in the eastern Mojave Desert, California. Desert Bighorn Council Transactions 36:41–47.

- Bleich, V. C., R. T. Bowyer, and J. D. Wehausen. 1997. Sexual segregation in mountain sheep: resources or predation? Wildlife Monographs 134:1–50.

- Bleich, V. C., M. W. Oehler, and R. T. Bowyer. 2017. Mineral content of forage plants of mountain sheep, Mojave Desert, USA. California Fish and Game 103:55–65.

- Bleich, V. C., B. M. Pierce, J. T. Villepique, and H. B. Ernest. 2019. Serum chemistry of wild, free-ranging mountain lions (Puma concolor) in the eastern Sierra Nevada, California, USA. California Fish and Game 105:72–86.

- Borch-Iohnsen, B., and K. J. Nilssen. 1987. Seasonal iron overload in Svalbard reindeer liver. Journal of Nutrition 117:2072–2078.

- Bowyer, R. T. 1983. Osteophagia and antler breakage among Roosevelt elk. California Fish and Game 62:84–88.

- Burton, C. A., T. M. Hoefen, G. S. Plumlee, K. L. Baumberger, A. R. Backlin, E. Gallegos, and R. N. Fisher. 2016. Trace elements in stormflow, ash, and burned soil following the 2009 Station Fire in Southern California. PLOS ONE 11:e0153372.

- Bush, A. P. 2015. Mule deer demographics and parturition site selection: assessing responses to provision of water. Thesis, University of Nevada Reno, Reno, NV, USA.

- Butler, O. M., J. J. Elser, T. Lewis, B. Mackey, and C. Chen. 2018. The phosphorus-rich signature of fire in the soil–plant system: a global meta-analysis. Ecology Letters 21:335–344.

- California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG). 2007. Wildlife restraint handbook. California Department of Fish and Game, Wildlife Investigations Laboratory, Rancho Cordova, CA, USA.

- Carlisle, D., and G. B. Cleveland. 1958. Plants as a guide to mineralization. California Division of Mines Special Report 50. California Division of Mines, San Francisco, CA, USA.

- Casebier, D. G. 2005. The great Mojave National Preserve fire, 22–27 June 2005. The Guzzler, 4 August 2005. Available from: http://theguzzler.blogspot.com/2005/08/great-mojave-national-preserve-fire.html (Accessed 6 March 2022)

- Chitwood, M. C., C. S. DePerno, J. R. Flowers, and S. Kennedy-Stoskopf. 2013. Physiological condition of female white-tailed deer in a nutrient-deficient habitat type. Southeastern Naturalist 12:307–316.

- Cook, R. C., J. G. Cook, T. R. Stephenson, W. L. Myers, S. M. McCorquodale, D. J. Vales, L. L. Irwin, P. B. Hall, R. D. Spencer, S. L. Murphie, K. A. Schoenecker, and P. J. Miller. 2010. Revisions of rump fat and body scoring indices for deer, elk, and moose. Journal of Wildlife Management 74:880–896.

- Cook, R. C., T. R. Stephenson, W. L. Myers, J. G. Cook, and L. A. Shipley. 2007. Validating predictive models of nutritional condition for mule deer. Journal of Wildlife Management 71:1934–1943.

- De Rosales, A. R., D. S. Siripala, S. Bodana, F. Ahmad, and D. R. Kumbala. 2017. Pseudohyperkalemia: look before you treat. Saudi Journal of Kidney Disease Transplantation 28:410–414.

- DelGiudice, G. D., P. R. Krausman, E. S. Bellantoni, M. C. Wallace, R. C. Etchberger, and U. S. Seal. 1990. Blood and urinary profiles of free-ranging desert mule deer in Arizona. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 26:83–89.

- Downs, C. J., and K. M. Stewart. 2014. A primer in ecoimmunology and immunology for wildlife research and management. California Fish and Game 100:371–395.

- Duffy, L. K., M. W. Oehler, R. T. Bowyer, and V. C. Bleich. 2009. Mountain sheep: an environmental epidemiological survey of variation in metal exposure and physiological biomarkers following mine development. American Journal of Environmental Sciences 5:296–303.

- Ellervik, C., and J. Vaught. 2015. Preanalytical variables affecting the integrity of human biospecimens in biobanking. Clinical Chemistry 61:914–934.

- Failla, M. L. 2003. Trace elements and host defense: recent advances and continuing challenges. Journal of Nutrition 133:1443S–1447S.

- Flynn, A., A. W. Franzmann, P. D. Arneson, and J. L. Oldemeyer. 1977. Indications of copper deficiency in a subpopulation of Alaskan moose. Journal of Nutrition 107:1182–1189.

- Flueck, W. T. 1991. Whole blood selenium levels and glutathione peroxidase activity in erythrocytes of black-tailed deer. Journal of Wildlife Management 55:26–31.

- Frank, I. A., A. V. Galgan, and L. R. Petersson. 1994. Secondary copper deficiency, chromium deficiency, and trace element imbalance in the moose: effect of anthropogenic activity. Ambio 23:315–317.

- French, C. E., L. C. McEwen, N. D. Magruder, R. H. Ingram, and R. W. Swift. 1956. Nutrient requirements for growth and antler development in the white-tailed deer. Journal of Wildlife Management 20:221–232.

- Friedrichs, K. R., K. E. Harr, K. P. Freeman, B. Szladovits, R. M. Walton, K. F. Barnhart, and J. Blanco-Chavez. 2012. ASVCP reference interval guidelines: determination of de novo reference intervals in veterinary species and other related topics. Veterinary Clinical Pathology 41:441–453.

- Gannon, W. L., and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists. 2007. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. Journal of Mammalogy 88:809–823.

- Garcia-Marco, S., and S. Gonzalez-Prieto. 2008. Short- and medium-term effects of fire and fire-fighting chemicals on soil micronutrient availability. Science of the Total Environment 407:297–303.

- Gartner, R. J. W., J. W. Ryley, and W. A. Beattie. 1965. The influence of degree of excitation on certain blood constituents in beef cattle. Australian Journal of Experimental Biology and Medical Science 43:713–724.

- Greene, L. W., W. E. Pinchak, and R. K. Heitschmidt. 1987. Seasonal dynamics of minerals in forages at the Texas experimental ranch. Journal of Range Management 40:502–506.

- Greffre, A., D. Concordet, J.-P. Braun, and C. Trumel. 2011. Reference Value Advisor: a new freeware set of 164 macroinstructions to calculate reference intervals with Microsoft Excel. Veterinary Clinical Pathology 40:107–112.

- Greffre, A., K. Friedrichs, K. Harr, D. Concordet, C. Trumel, and J.-P. Braun. 2009. Reference values: a review. Veterinary Clinical Pathology 38:288–298.

- Hamerlynck, E. P., T. P. Huxman, M. E. Loik, and S. D. Smith. 2000. Effects of extreme high temperature, drought and elevated CO2 on photosynthesis of the Mojave Desert evergreen shrub, Larrea tridentata. Plant Ecology 148:183–193.

- Hantson, S., T. P. Huxman, S. Kimball, J. T. Randerson, and M. L. Goulden. 2021. Warming as a driver of vegetation loss in the Sonoran Desert of California. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 126:e2020JG005942.

- Harrison, P. D., and M. I. Dyer. 1984. Lead in mule deer forage in Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado. Journal of Wildlife Management 48:510–517.

- Heffelfinger, J. R., and E. K. Latch. 2023. Origin, classification, and distribution. Pages 3–24 in J. R. Heffelfinger and P. R. Krausman, editors. Ecology and Management of Black-tailed and Mule Deer of North America. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA.

- Heffelfinger, L., K. M. Stewart, A. P. Bush, J. Sedinger, N. Darby, and V. C. Bleich. 2018. Timing of precipitation in an arid environment: effects on population performance of a large herbivore. Ecology and Evolution 8:3354–3366.

- Heffelfinger, L. J., K. M. Stewart, K. T. Shoemaker, N. W. Darby, and V. C. Bleich. 2020. Balancing current and future reproductive investment: variation in resource selection during stages of reproduction in a long-lived herbivore. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8:163.

- Hernandez, F., R. E. Oldenkamp, S. Webster, J. C. Beasley, L. L. Farina, and S. M. Wisely. 2017. Raccoons (Procyon lotor) as sentinels of trace element contamination and physiological effects of exposure to coal fly ash. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 72:235–246.

- Herrada, A., L. Bariod, S. Said, B. Rey, H. Bidault, Y. Bollet, S. Chabot, F. Dedbias, J. Duhayer, S. Pardonnet, M. Pellerin, J.-B. Fanjul, C. Rousset, C. Fritsch, N. Crini, R. Scheifler, G. Bourgoin, and P. Vuarin. 2024. Minor and trace element concentrations in roe deer hair: a non-invasive method to define reference values in wildlife. Ecological Indicators 159:111720.

- Holl, S. A., and V. C. Bleich. 1987. Mineral lick use by mountain sheep in the San Gabriel Mountains, California. Journal of Wildlife Management 51:383–385.

- Hunt, C. B. 1966. Plant ecology of Death Valley, California. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 509. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., USA.

- Jensen, W. F., V. C. Bleich, and D. G. Whittaker. 2023. Historical trends in black-tailed deer, mule deer, and their habitats. Pages 25–42 in J. R. Heffelfinger and P. R. Krausman, editors. Ecology and Management of Black-tailed and Mule Deer of North America. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA.

- Johnson, H. E., V. C. Bleich, and P. R. Krausman. 2005. Antler breakage in tule elk, Owens Valley, California. Journal of Wildlife Management 69:1747–1752.

- Johnson, H. E., V. C. Bleich, and P. R. Krausman. 2007. Mineral deficiencies in tule elk, Owens Valley, California. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 43:61–74.

- Kalisinska, E. 2019. Mammals and Birds as Bioindicators of Trace Element Contaminations in Terrestrial Environments: An Ecotoxicological Assessment of the Northern Hemisphere. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland.

- Kaspari, M. 2021. The invisible hand of the periodic table: how micronutrients shape ecology. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 52:199–219.

- Kie, J. G., M. White, and D. L. Drawe. 1983. Condition parameters of white-tailed deer in Texas. Journal of Wildlife Management 47:583–594.

- Keating, K. A. 1989. Bone chewing by Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep. Great Basin Naturalist 50:89.

- Kock, M. D., D. A. Jessup, R. K. Clark, and C. E. Franti. 1987. Effects of capture on biological parameters in free-ranging bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis): evaluation of drop-net, drive-net, chemical immobilization and net-gun. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 23:641–651.

- Krausman, P. R., and J. A. Bissonette. 1977. Bone chewing behavior of the desert mule deer. Southwestern Naturalist 22:149–150.

- Krausman, P. R., J. J. Hervert, and L. L. Ordway. 1985. Capturing deer and mountain sheep with a net-gun. Wildlife Society Bulletin 13:71–73.

- Lisk, D. J. 1972. Trace metals in soils, plants, and animals. Advances in Agronomy 24:267–325.

- McAuliffe, J. R. 2021. Storm cloud over Cima Dome—tracking vegetation change after the fire. Mojave National Preserve Science Newsletter 2021:1–11. Available from: https://www.nps.gov/moja/learn/science-newsletter.htm (Accessed 18 March 2022)

- McDowell, L. R. 2003. General introduction. Pages 1–32 in L. R. McDowell, editor. Minerals in Animal and Human Nutrition. 2nd edition. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- McKee, C. J., K. M. Stewart, J. S. Sedinger, A. P. Bush, N. W. Darby, D. L. Hughson, and V. C. Bleich. 2015. Spatial distributions and resource selection by mule deer in an arid environment: responses to provision of water. Journal of Arid Environments 122:76–84.

- Mule Deer Working Group (MDWG). 2004. North American mule deer conservation plan. Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, Cheyenne, WY, USA.

- Merrill, E. H., H. F. Mayland, and J. M. Peek. 1980. Effects of fall wildfire on herbaceous vegetation on xeric sites in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, Idaho. Journal of Range Management 33:363–367.

- Monteith, K. L., T. N. LaSharr, C. J. Bishop, T. R. Stephenson, K. M. Stewart, and L. A. Shipley. 2023. Digestive physiology and nutrition. Pages 71–94 inJ. R. Heffelfinger and P. R. Krausman, editors. Ecology and Management of Black-tailed and Mule Deer of North America. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA.

- Monteith, K. L., T. R. Stephenson, V. C. Bleich, M. M. Conner, B. M. Pierce, and R. T. Bowyer. 2013. Risk-sensitive allocation in seasonal dynamics of fat and protein reserves in a long-lived mammal. Journal of Animal Ecology 82:377–388.

- Myers, W. L., W. J. Foreyt, P. A. Talcott, J. F. Evermann, and W.-Y. Chang. 2015. Serologic, trace element, and fecal parasite survey of free-ranging, female mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in eastern Washington, USA. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 51:125–136.

- O’Hara, T. M., G. Carroll, P. Barboza, K. Mueller, J. Blake, V. Woshner, and C. Willeto. 2001. Mineral and heavy metal status as related to a mortality event and poor recruitment in a moose population in Alaska. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 37:509–522.

- Ohr, K. M., and T. B. Bragg. 1985. Effects of fire on nutrient and energy concentration of five prairie grass species. Prairie Naturalist 17:113–126.

- Oliver, M. N., G. Ros-McGauran, D. A. Jessup, B. B. Norman, and C. E. Franti. 1990. Selenium concentrations in blood of free-ranging mule deer in California. Transactions of the Western Section of The Wildlife Society 26:80–86.

- Pierce, B. M., and V. C. Bleich. 2003. Mountain lion. Pages 744–757 in G. A. Feldhamer, B. C. Thompson, and J. A. Chapman, editors. Wild Mammals of North America. 2nd edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, USA.

- Pond, W. G., D. C. Church, K. R. Pond, and P. A. Schoknecht. 2005. Basic animal nutrition and feeding. 5th edition. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, NJ, USA.

- Poppenga, R. H., J. Ramsey, B. J. Gonzales, and C. K. Johnson. 2012. Reference intervals for mineral concentrations in whole blood and serum of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in California. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 24:531–538.

- Puls, R. 1994. Mineral Levels in Animal Health: Diagnostic Data. 2nd edition. Sherpa International, Clearbrook, British Columbia, Canada.

- Radostits, O. M., C. C. Gay, K. W. Kinchcliff, and P. D. Constable. 2007. Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Horses, Sheep, Pigs and Goats. 10th edition. Saunders Elsevier, Edinburgh, UK.

- Reeves, A. M., S. S. Gray, J. C. Campbell, L. A. Harveson, C. D. Hilton, L. J. Heffelfinger, C. M. Springer, D. G. Hewitt, W. C Conway, and R. O. Dittmar II. 2024. Hematology and biochemical reference intervals and seroprevalence of hemorrhagic diseases for free-ranging mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in west Texas. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 55:1019–1031.

- Robbins, C. T. 1993. Wildlife Feeding and Nutrition. 2nd edition. Academic Press, London, UK.

- Robbins, C. T., S. M. Parish, and B. L. Robbins. 1985. Selenium and glutathione peroxidase activity in mountain goats. Canadian Journal of Zoology 63:1544–1547.

- Rosen, L. E., D. P. Walsh, L. L. Wolfe, C. L. Bedwell, and M. W. Miller. 2009. Effects of selenium supplementation and storage time on blood indices of selenium status in bighorn sheep. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 45:795–801.

- Roug, A., P. K. Swift, G. Gerstenberg, L. W. Woods, C. Kreuder-Johnson, S. G. Torres, and B. Puschner. 2015. Comparison of trace mineral concentrations in tail hair, body hair, blood, and liver of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in California. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 27:295–305.

- Rundel, P. W., and A. C. Gipson. 1996. Ecological Communities and Processes in a Mojave Desert Ecosystem. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, NY, USA.

- Sikes, R. S., and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists. 2011. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. Journal of Mammalogy 92:235–253.

- Sikes, R. S., and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists. 2016. 2016 Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education. Journal of Mammalogy 97:663–688.

- Sprinkle, J. E., E. J. Bicknell, T. H. Noon, C. Reggiardo, D. F. Perry, and H. M. Frederick. 2000. Variation in trace minerals in forage by seasons and species and the effects of mineral supplementation upon beef cattle production. Proceedings of the Western Section of the American Society of Animal Science 51:276–280.

- Staaland, H., and K. Hove. 2000. Seasonal changes in sodium metabolism in reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) in an inland area of Norway. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 32:286–294.

- Staaland, H., and R. G. White. 2001. Regional variation in the mineral contents of plants and its significance for migration by Arctic reindeer and caribou. Alces 37:497–509.

- Stephenson, T. R., V. C. Bleich, B. M. Pierce, B. and G. P. Mulcahy. 2002. Validation of mule deer body composition using in vivo and postmortem indices of nutritional condition. Wildlife Society Bulletin 30: 557–564.

- Stephenson, T. R., J. W. Testa, G. P. Adams, R. G. Sasser, C. C. Schwartz, and K. J. Hundertmark. 1995. Diagnosis of pregnancy and twinning in moose by ultrasonography and serum assay. Alces 31:167–172.

- Thomas, K., T. Keeler-Wolf, J. Franklin, and P. Stine. 2004. Mojave Desert ecosystem program: central Mojave vegetation database. U.S.G.S. Western Ecological Research Center and Southwest Biological Science Center, Sacramento, CA, USA.

- Thorne, R. F., B. A. Prigge, and J. Henrickson. 1981. A flora of the higher ranges and the Kelso Dunes of the eastern Mojave Desert in California. ALISO 10:71–186.

- Thornton, C. 2023. York wildfire still blazing, threatening Joshua trees in Mojave Desert. USA Today, 2 August 2023. Available from: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2023/08/02/california-york-fire-update/70511816007/ (Accessed 21 February 2024)

- Van Soest, P. J. 1994. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant. 2nd edition. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Wallmo, O. C. 1981. Mule and black-tailed deer distribution and habitats. Pages 1–25 in O. C. Wallmo, editor. Mule and Black-tailed Deer of North America. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE, USA.

- Warrick, G., and P. R. Krausman. 1986. Bone-chewing by desert bighorn sheep. Southwestern Naturalist 31:414.

- Zar, J. H. 2010. Biostatistical Analysis, 5th edition. Prentice-Hall Press, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA.

- Zimmerman, T. J., J. A. Jenks, D. M. Leslie, Jr., and R. D. Neiger. 2008. Hepatic minerals of white-tailed and mule deer in the southern Black Hills, South Dakota. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 44:341–350.