On the importance of agriculture for wildlife conservation

ESSAY

Matt Johnson*

California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, Wildlife Department, 1 Harpst Street, Arcata, CA 95521, USA  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3662-2824

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3662-2824

*Corresponding Author: mdj6@humboldt.edu

Published 28 August 2025 • doi.org/10.51492/cfwj.111.12

Key words: agriculture, biodiversity, conservation, defaunation, farming, wildlife

| Citation: Johnson, M. 2025. On the importance of agriculture for wildlife conservation. California Fish and Wildlife Journal 111:e12. |

| Editor: Ange Darnell Baker, Habitat Conservation Planning Branch |

| Submitted: 13 April 2025; Accepted: 9 May 2025 |

| Copyright: ©2025, Johnson. This is an open access article and is considered public domain. Users have the right to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles in this journal, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, provided the authors and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife are acknowledged. |

| Competing Interests: The author has not declared any competing interests. |

The primacy of agriculture

Wild animals are imperiled, with a high rate of species extinction and the decline of once-abundant species. Meanwhile, we are simultaneously grappling with human-caused climate change and struggling to feed a growing human population; and these three individual challenges all interact (Travis 2003). This is the triple crisis of the Anthropocene (Kremen and Merenlender 2018). In this essay, I argue that how we manage the world’s agricultural lands—the farms and rangelands that sustain our food supply—will play a decisive role in addressing this interlinked crisis. I assert that we, as wildlife biologists, must give more focused attention to efforts that integrate agriculture and wildlife conservation, both to keep common species common and to avert extinction.

What is the single greatest cause for wildlife species endangerment in the world? For the majority of endangered species on the planet, including most of those in California, the main cause of their endangerment is habitat loss and degradation, collectively called habitat alteration (Pimm and Raven 2000; CDFG 2005; Johnson 2005; IBPES 2019). And what drives habitat alteration? In a word: agriculture. Data from International Union for the Conservation of Nature indicate that the single greatest cause of habitat alteration for threatened species worldwide is agricultural expansion (IUCN 2024). Indeed, 37% of the Earth’s terrestrial landmass is devoted to agriculture (Foley et al. 2007), in California that figure is 40%, counting grazed rangelands (PPIC 2024). The rate of habitat loss due to urbanization and infrastructure is far less, though it is rising quickly (Maxwell et al. 2016; IBPES 2019). The ecological footprint of developed areas is, of course, much larger than their literal acreage, but these impacts arise primarily because of the food, energy, and materials required to feed and house the people within them, reiterating the primacy of agriculture. In short, habitat alteration is the most common threat to special status wildlife species, and unsustainable agriculture is largely to blame.

Agriculture not only drives habitat loss that affects wildlife species; it also underlies the causes of global climate change, which threatens the environment writ large (Hulme et al. 2018). Human-caused climate change will likely not only impact biodiversity, but it will also usher new and unpredictable natural disasters, challenge crop production, and exacerbate human inequity and global conflict (Pörtner et al. 2023). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change attributes global greenhouse gas emissions to six sectors of the global economy: electricity and heat production, other energy production, buildings, industry, transportation, and agriculture (Edenhofer et al. 2015). They estimate that agriculture, including industrial plantation forestry and associated land use change, contributes 24% to global greenhouse gas emissions (Smith et al. 2014). But of course, a fraction of the other sectors—especially transportation, industry, and electricity production—is explicitly for food production and distribution, so when we consider the up and downstream components of the global food and agricultural systems overall, this percentage rises to 33% (Smith et al. 2014). Thus, we see that agriculture is the primary driver of biodiversity loss, and it is arguably the largest contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions.

What can we say about the future of agriculture? Have we reached sustainable food production for the global population? Not even close. Current estimates suggest that global crop demand is expected to increase 35–56% by 2050 (Van Dijk et al. 2021). This rise is of course partly due to the increasing human population, but it is also propelled by increasing per capita consumption and people eating higher on the food chain. How will we meet that demand? Ideally, we will actively work to diminish demand by continuing to decelerate population growth rate and eating lower on the food chain. We are working also on decreasing food waste and improved global food distribution (Parfitt et al. 2010; Khoury et al. 2014). But we have to be realistic, those efforts alone will not meet rising demand. We will almost certainly need to increase the area devoted to agriculture (Davis et al. 2016), enhance sustainable production on areas already in cultivation (Foley et al. 2011), and—importantly—reduce crop losses to pests and disease, which are currently estimated at about 30% globally (Oerke 2006).

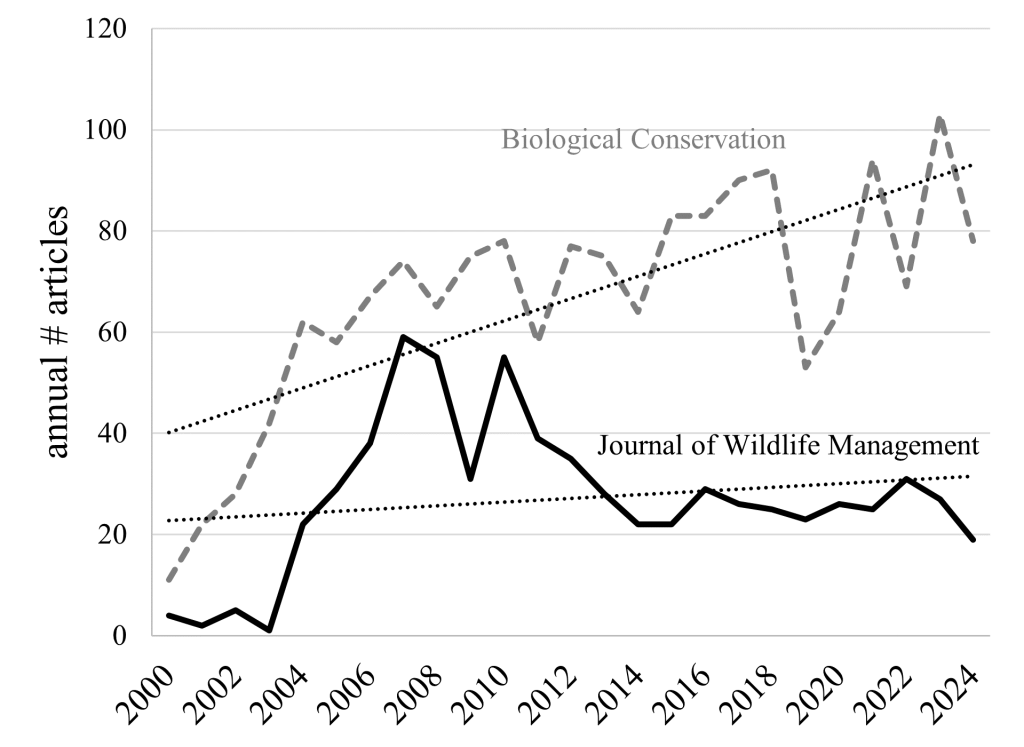

So, with all this evidence pointing to an urgent need to integrate agriculture and wildlife conservation, we might expect that our societies and journals are sharply focused on this issue. Indeed, many big international non-governmental organizations have, in the last 20 years, launched campaigns specifically focused on integrating the needs of sustainable agricultural production with wildlife and fish conservation (Scherr and McNeely 2008; Frizo and Niederle 2021). And some journals show a corresponding sharp rise in the frequency of papers connecting wildlife conservation with agriculture. A quick search for the annual number of papers since 2000 with key words related to agriculture showed a steady upward march in some journals, such as Biological Conservation (Fig. 1). But not all journals show that trend; the Journal of Wildlife Management showed a peak of papers mentioning agriculture in the early 2000s, but over the last quarter century the rate has remained overall relatively flat.

We might also expect the curricula of university wildlife programs to intentionally incorporate agricultural topics. In a quick review of the universities offering Bachelor’s degrees in Wildlife in the Western Section of The Wildlife Society (California, Nevada, and Hawaii[1]), there appears to be little explicit attention to agriculture in their wildlife curricula. While these campuses each have sustainable agricultural programs, those courses do not appear to be very well connected to the wildlife programs on those campuses. Of course, the topic of agriculture undoubtedly appears within individual wildlife courses. This is true in my own Habitat Ecology course at Cal Poly Humboldt and probably in most universities’ Conservation Biology courses, but it appears that only UC Davis has a full agrocecology course within its wildlife program.

I contend this is a shortcoming. As I have outlined, agriculture is foundational to observed losses of biodiversity, and it is crucial for the future of wildlife conservation. I argue that neither The Wildlife Society nor our university curricula are giving it enough attention. A recent session at the 2025 meeting of the Western Section of The Wildlife Society is a step in the right direction, but much more can and should be done, a point I will return to later in this essay.

An imperative to keep common animals common

We are in the midst of the planet’s sixth mass extinction, and the discipline of wildlife conservation has justifiably put attention on averting the loss of critically endangered species. The U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2023, and the work of wildlife biologists is now deeply interwoven with this vital piece of legislation (Schwartz 2008; Owen 2019). Indeed, the rise and prominence of consulting firms in California has been driven by mitigation and compliance: Companies and developers need consultants to conduct biological surveys, habitat assessments, and mitigation planning to comply with laws like the ESA, National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). I of course join the legion of conservation biologists working to keep species from vanishing from the Earth. Extinction is a visceral tragedy—a final loss from which there is no return. The loss of letting a unique species disappear is eternal. But it is not the only biological tragedy we are contending with.

We’re not just losing the ‘diversity’ in biodiversity—we’re losing the ‘bio’ too: the raw abundance of life on Earth (Jarvis 2018). As the entomologist David Wagner suggests, “We notice the losses, it’s the diminishment that we don’t see” (cited in Jarvis 2018). Still abundant but declining species trigger comparatively little protection. Our unwavering attention to species extinction has unfortunately dampened our response to an equally disturbing trend—the raw loss of abundance of animals with whom we share this planet.

Dirzo et al. (2014) articulated the concept of “defaunation” which they contend should become as familiar, and influential, as the concept of deforestation. Just as deforestation refers to loss of forest cover as well as the loss of tree species, defaunation is defined as the loss and decline of animal species and the number of individual animals in a region. And let us be clear, the planet is hemorrhaging its abundance of vertebrates. The World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Report, substantiated also by Dirzo et al.’s work, suggest a 28% reduction in wildlife populations worldwide over the last 50 years (WWF 2024). Rosenberg et al. (2019) showed that we have lost almost 3 billion birds over the same timeframe. Many of these species are still relatively common, and thus don’t trigger any protection from endangered species legislation, but they are a shadow of what they once were, and our landscapes and lives our diminished accordingly. And this tragedy extends beyond vertebrates. Evidence especially in Europe but increasingly also from North America suggests a staggering 30–60% loss of flying insects, termed the Insect Apocalypse (Forister et al. 2011; van Klink et al. 2024). The reasons for these declines are complex, but insecticide use in agriculture and habitat loss from agricultural intensification are centerpiece to an array of threats (Goulson 2019).

The evidence was never clearer; we are in a new epoch. As data from Bar-On et al. (2018) poignantly illustrate, humans dominate the planet. The biomass of humans now far outweighs all the wild mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians combined. Add our livestock to our total, and that collective weight is more than 12 times larger than all terrestrial vertebrate wildlife on the planet.

Hope

With this unvarnished look at the profound and troubling effects of unstainable agriculture on wildlife, let us look to the future. And there is reason for hope. To avert continued losses, we must sharpen our focus on uniting food production with wildlife conservation. As the World Wildlife Fund suggests, it is not too late to transform our food system (WWF 2025). And we need everyone to contribute: the federal and state agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector. Here I briefly review examples of excellent work in each sector, not of course as an exhaustive review, but as evidence of what is possible.

The U.S. Farm Bill (its current version, formerly, The Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018) is an underappreciated piece of federal environmental legislation (WWF 2018). Begun in the New Deal era, it is up for renewal about every 5 years, including as I write; in the coming months Congress will grapple with reconciling House and Senate versions of a new Farm Bill, with important implications for conservation. While the Farm Bill is best known for funding nutrition programs (SNAP food stamps) and crop subsidies, it also allocates billions to conservation. In the 2018 version, this amounted to $29 billion for soil and wildlife conservation and climate resiliency (USDA 2025). This funding propels multiple programs administered by the Natural Resource Conservation Service, most famously the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) that now enrolls near 23 million acres, paying farmers to set aside otherwise farmed land for the benefit of soil, wildlife, and farmers alike (Haufler 2005, 2007). Indeed, The Nature Conservancy’s economic research shows these federal investments conservatively return $1.58 for every federal dollar invested, totaling more than $3.4 billion annually and annually supporting more than 46,000 jobs nationwide through 2029 if the bill is renewed intact (TNC 2025). As Congress debates the new Farm Bill, it is vital that our congress people recognize how valuable these programs are not just for biodiversity, but also for the economic wellbeing of rural American communities.

At the state level, we are fortunate to be here in California, which is a world leader in wildlife conservation. For example, wildlife researchers have long known about the dangerous secondary poisoning effects of first and especially second generation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs). In fall 2024, Governor Newsom signed Assembly Bill AB 2552 in law (California Legislative Information 2024), effectively banning the use of SGARs for agricultural purposes, thereby creating the strictest restriction on rodenticides in the nation (CBD 2024). The Williamson Act—officially the California Land Conservation Act of 1965—is a key policy tool that supports the conservation of working lands in ways that can also benefit biodiversity. By discouraging urban sprawl and habitat fragmentation, this act helps maintain large, contiguous tracts of habitat crucial for many wide-ranging animals like raptors and large carnivores. Although California does not have a state-run analog to the U.S. Farm Bill, it funds several agriculture and conservation programs that serve similar functions, particularly in promoting sustainable agriculture, habitat conservation, and climate resilience, such as the Healthy Soils Program (CDFA 2025), California Farmland Conservancy Program, and the Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation Program (CDOC 2025). These programs not only benefit biodiversity; they also propel more sustainable agriculture by improving soil quality, resilience to pests and disease, and drought tolerance (Pandu et al. 2025), further illustrating a win-win for biodiversity conservation and agriculture. If the federal government scales back its conservation agriculture programs, state-run programs may need to expand to sustain these benefits for California’s wildlife and farms.

In addition to federal and state governments, we need NGOs and the private sector. There are many amazing innovative ideas to bring farmers and conservation together, but here I’ll just highlight two. First, the highly successful BirdReturns project is a collaboration between The Nature Conservancy, California Audubon, and Point Blue Conservation Science (BirdReturns 2025). The goal of this program is to boost the numbers of migrating wetland birds, which they accomplish by incentivizing farmers to prepare and flood their fields at strategic times and places to coincide with waves of migrating birds. While most conservation efforts focus on acquiring or restoring habitat permanently removed from food production, BirdReturns flips this with a market-driven mechanism to create short-term, strategically timed wetlands on working rice fields in the Central Valley. Just in the last 10 years, the program has provided more than 60,000 acres of temporary wetlands, and field data show it is working to bolster the abundance of birds along the Pacific Flyway (Golet et al. 2018, 2022). Partners in Flight, a collaborative initiative that unites NGOs and agencies, also advances preventive conservation for species that are still abundant but declining, including birds reliant on open agricultural spaces (e.g., western meadowlark [Sturnella neglecta]and barn swallow [Hirundo rustica]).

Another NGO, called Wild Farm Alliance, works at the nexus of farming, education, and conservation science (WFA 2025). They have extensive educational resources for farmers aiming to invite wildlife onto their lands, and they have recently launched two new programs, called Farmland Wildways and Farmland Flyways to increase the number of hedgerows and nest boxes, respectively, on farms throughout the U.S. Beyond the obvious benefit to local wildlife, recent evidence shows birds attracted by these enhancements eat crop pests (WFA 2019; Dainese et al. 2019), demonstrating another win-win for biodiversity and farming. Wild Farm Alliance’s long-term vision is to prompt 25% of the nation’s farmers to plant native hedgerows that are, on average, 1 mile in length. If successful, this would create 500,000 miles of native hedgerows—roughly the distance from Earth to the moon and back. A lofty goal to be sure, but we need this kind of vision and ambition, and their vision should be applauded.

Too often, we frame agriculture and wildlife as adversaries. Either agriculture threatens wildlife through habitat loss and chemicals, or wildlife threatens agriculture by damaging crops. But there’s a third story—one of coexistence and mutual benefit. The American barn owl (Tyto furcata), still common and deeply entwined with agricultural landscapes, is a symbol of that possibility. Farmers can bolster owl populations with nest boxes (Roulin 2020; Johnson et al. 2025); the owls, in turn, help control pests—a mutualism that benefits both wildlife and agriculture (Hansen and Johnson 2022; Bontzorlos et al. 2024). For the last half century, much of the work pursued by The Wildlife Society and state wildlife agencies involved either listed species, game species, and/or the management of wildlife on public lands. There are good reasons for those emphases, but as I have argued here, much of the future of conservation will be painted on a canvas comprised of the world’s working lands – especially its farms and rangelands. Moreover, the sheer abundance of life on Earth is upheld by the commonest of animals, including barn owls. If we are to leave this planet to future generations with an abundance of wildlife, we must invest in keeping common species common—not just on public lands, but across the working landscapes that feed the world. Conservation and agriculture must not be viewed as opposites. As Aldo Leopold wrote, “When the land does well for its owner, and the owner does well by [their] land – when both end up better by reason of their partnership—then we have conservation” (Leopold 1949, p. 207–208).

Literature Cited

- Bar-On, Y. M., R. Phillips, and R. Milo. 2018. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:6506–6511.

- BirdReturns 2025. Delivering habitat for migratory birds along the Pacific Flyway Available from https://birdreturns.org/.

- Bontzorlos, V., S. Cain, Y. Leshem, O. Spiegel, Y. Motro, I. Bloch, S. I. Cherkaoui, S. Aviel, M. Apostolidou, A. Christou, and H. Nicolaou. 2024. Barn owls as a nature-based solution for pest control: a multinational initiative around the Mediterranean and other regions. Conservation 4:627–656.

- California Department of Conservation (CDOC) 2025. California Farmland Conservation Program. Available from: https://www.conservation.ca.gov/dlrp/grant-programs/Pages/Index.aspx

- California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG). 2005. The Status of Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Plants and Animals of California, 2000–2004. Available from: https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/CESA/Summary-Reports#566973108-2005-report

- California Department of Food and Agricultural (CDFA) 2025. Office of Agricultural Resilience and Sustainability. Available from: https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/oars/onfarm-funding/.

- California Legislative Information. 2024. California Assembly Bill No. 2552. Available from: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=202320240AB2552

- Center for Biological Diversity (CBD). 2024. California OKs Strongest Rat Poison Restrictions in Nation. Press Release 25 Sept 2024. Available from: https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/california-oks-strongest-rat-poison-restrictions-in-nation-2024-09-25/

- Dainese, M., E. A. Martin, M. A. Aizen, M. Albrecht, I. Bartomeus, R. Bommarco, L. G. Carvalheiro, R. Chaplin-Kramer, V. Gagic, L. A. Garibaldi, and J. Ghazoul. 2019. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity-mediated benefits for crop production. Science Advances: 5:eaax0121.

- Davis, K. F., J. A. Gephart, K. A. Emery, A. M. Leach, J. N. Galloway, and P. D’Odorico. 2016. Meeting future food demand with current agricultural resources. Global Environmental Change 39:125–132.

- Dirzo, R., H. S. Young, M. Galetti, G. Ceballos, N. J. Isaac, and B. Collen. 2014. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 345:401–406.

- Edenhofer, O., editor. 2015. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Volume 3. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Foley, J. A., C. Monfreda, N. Ramankutty, and D. Zaks. 2007. Our share of the planetary pie. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104:12585–12586.

- Foley, J. A., N. Ramankutty, K. A. Brauman, E. S. Cassidy, J. S. Gerber, M. Johnston, N. D. Mueller, C. O’Connell, D. K. Ray, P. C. West, and C. Balzer. 2011. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 478: 337–342.

- Forister, M. L., J. P. Jahner, K. L. Casner, J. S. Wilson, A. M. and Shapiro. 2011. The race is not to the swift: long‐term data reveal pervasive declines in California’s low‐elevation butterfly fauna. Ecology 92:2222–2235.

- Frizo, P. and P. Niederle. 2021. Institutional foundations for environmental conservation: an analysis of nongovernmental organizations’ engagement strategies in the Amazon. Review of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Studies 102:349–367.

- Golet, G. H., C. Low, S. Avery, K. Andrews, C. J. McColl, R. Laney, and M. D. Reynolds. 2018. Using ricelands to provide temporary shorebird habitat during migration. Ecological Applications 28:409–426.

- Golet, G. H., K. E. Dybala, M. E. Reiter, K. A. Sesser, M. Reynolds, and R. Kelsey. 2022. Shorebird food energy shortfalls and the effectiveness of habitat incentive programs in record wet, dry, and warm years. Ecological Monographs 92:e1541.

- Goulson, D. 2019. The insect apocalypse, and why it matters. Current Biology 29: R967–R971.

- Hansen, A., and M. Johnson. 2022. Evaluating the use of barn owl nest boxes for rodent pest control in winegrape vineyards in Napa Valley. Paper No. 27 in D. M. Woods, editor. Proceedings of the 30th Vertebrate Pest Conference. University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources, Davis, CA, USA.

- Haufler, J. B., editor. 2005. Fish and wildlife benefits of Farm Bill conservation programs: 2000–2005 update. The Wildlife Society Technical Review 05-2.

- Haufler, J.B., editor. 2007. Fish and wildlife response to Farm Bill conservation practices. The Wildlife Society Technical Review 07–1.

- Hulme, M., N. Obermeister, S. Randalls, and M. Borie. 2018. Framing the challenge of climate change in Nature and Science editorials. Nature Climate Change 8:515–521.

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) 2024. Agriculture and conservation. Switzerland. Available from: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/51576

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) 2019. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, and H. T. Ngo, editors. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673

- Jarvis, B. 2018. The insect apocalypse is here. The New York Times Magazine, 27 Nov 2018. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/27/magazine/insect-apocalypse.html

- Johnson, M. D. 2005. Habitat quality: a brief review for wildlife biologists. Transactions-Western Section of the Wildlife Society 41:31–41.

- Johnson, M. D., J. E. Carlino, S. D. Chavez, R. Wang, C. Cortez, L. M. Echávez Montenegro, D. Duncan, and B. Ralph. 2025. Balancing model specificity and transferability: barn owl nest box selection. Journal of Wildlife Management 89:e22712.

- Khoury, C. K., A. D. Bjorkman, H. Dempewolf, J. Ramirez-Villegas, L. Guarino, A. Jarvis, L. H. Rieseberg, and P. C. Struik. 2014. Increasing homogeneity in global food supplies and the implications for food security. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111:4001–4006.

- Larson, K. C. 2024. Barn owls exert top-down effects on the abundance and behavior of rodent pests. Thesis, California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, Arcata, CA, USA.

- Leopold, A. 1949. A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Kremen, C., and A. M. Merenlender. 2018. Landscapes that work for biodiversity and people. Science 362:eaau6020.

- Maxwell, S. L., R. A. Fuller, T. M. Brooks, and J. E. M. Watson. 2016. Biodiversity: the ravages of guns, nets and bulldozers. Nature 536:143–145.

- Oerke, E. C., 2006. Crop losses to pests. Journal of Agricultural Science 144:31–43.

- Owen, D. 2019. Consultants, the environment, and the law. Arizona Law Review 61:823–844.

- Pandu, U., J. Nethra, M. C. S. Rao, and P. A. Varshini. 2025. Regenerative agriculture and soil conservation: a comprehensive review. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 15:295–304.

- Parfitt, J., M. Barthel, and S. Macnaughton. 2010. Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365:3065–3081.

- Pimm, S. L. and P. Raven. 2000. Extinction by numbers. Nature 403:843–845.

- Pörtner, H. O., R. J. Scholes, A. Arneth, D. K. A. Barnes, M. T. Burrows, S. E. Diamond, C. M. Duarte, W. Kiessling, P. Leadley, S. Managi, and P. McElwee. 2023. Overcoming the coupled climate and biodiversity crises and their societal impacts. Science 380:eabl4881.

- Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC). 2024. Agricultural land use in California. Available from: https://www.ppic.org/publication/agricultural-land-use-in-california/

- Roulin, A. 2020. Barn Owls: Evolution and Ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Rosenberg, K. V., A. M. Dokter, P. J. Blancher, J. R. Sauer, A. C. Smith, P. A. Smith, J. C. Stanton, A. Panjabi, L. Helft, M. Parr, and P. P. Marra. 2019. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366:120–124.

- Scherr, S. J., and J. A. McNeely. 2008. Biodiversity conservation and agricultural sustainability: towards a new paradigm of ‘ecoagriculture’ landscapes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 363:477–494.

- Schwartz, M. W. 2008. The performance of the endangered species act. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 39:279–299.

- Smith, P., and M. Bustamante. 2015. Agriculture, forestry and other land use. Pages 811–922 in O. Edenhofer, R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, J. C. Minx, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, J. Savolainen, and T. Zwickel, editors. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA.

- The Nature Conservancy (TNC). 2024. What you need to know about the Farm Bill. Available from: https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/our-priorities/provide-food-and-water-sustainably/food-and-water-stories/supporting-the-farm-bill/

- Travis, J. M. J., 2003. Climate change and habitat destruction: a deadly anthropogenic cocktail. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 270: 467–473.

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2025. Economic Research Service. 2018 Farm Bill. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-bill/2018-farm-bill

- Van Dijk, M., T. Morley, M. L. Rau, and Y. Saghai. 2021. A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010–2050. Nature Food 2:494–501.

- van Klink, R., D. E. Bowler, K. B. Gongalsky, M. Shen, S. R. Swengel, and J. M. Chase. 2024. Disproportionate declines of formerly abundant species underlie insect loss. Nature 628:359–364.

- Wild Farm Alliance (WFA). 2019. Supporting beneficial birds and managing pest birds. Available from: https://www.wildfarmalliance.org/supporting_beneficial_birds_and_managing_pest_birds_resource

- Wild Farm Alliance (WFA). 2025. Inspiring farmers. Cultivating biodiversity. Growing the movement. Available from: https://www.wildfarmalliance.org/

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). 2018. 5 Reasons the Farm Bill Matters to Conservation. Available from: https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/5-reasons-the-farm-bill-matters-to-conservation

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). 2024. Living Planet Report 2024 – A System in Peril.World Wildlife Fund, Gland, Switzerland.

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). 2025. Solving the nature loss crisis: what needs to change? Available from: https://livingplanet.panda.org/en-US/nature-recovery-solutions/

[1] California Polytechnic University, Humboldt (BS in Wildlife); California Polytechnic University; San Luis Obispo (Wildlife concentration in BS Environmental Management and Protection); University of California at Davis (BS Wildlife, Fisheries, and Conservation Biology); University of Nevada at Reno (BS Wildlife Ecology and Conservation); University of Hawaii at Manoa (Wildlife concentration in BS Zoology)